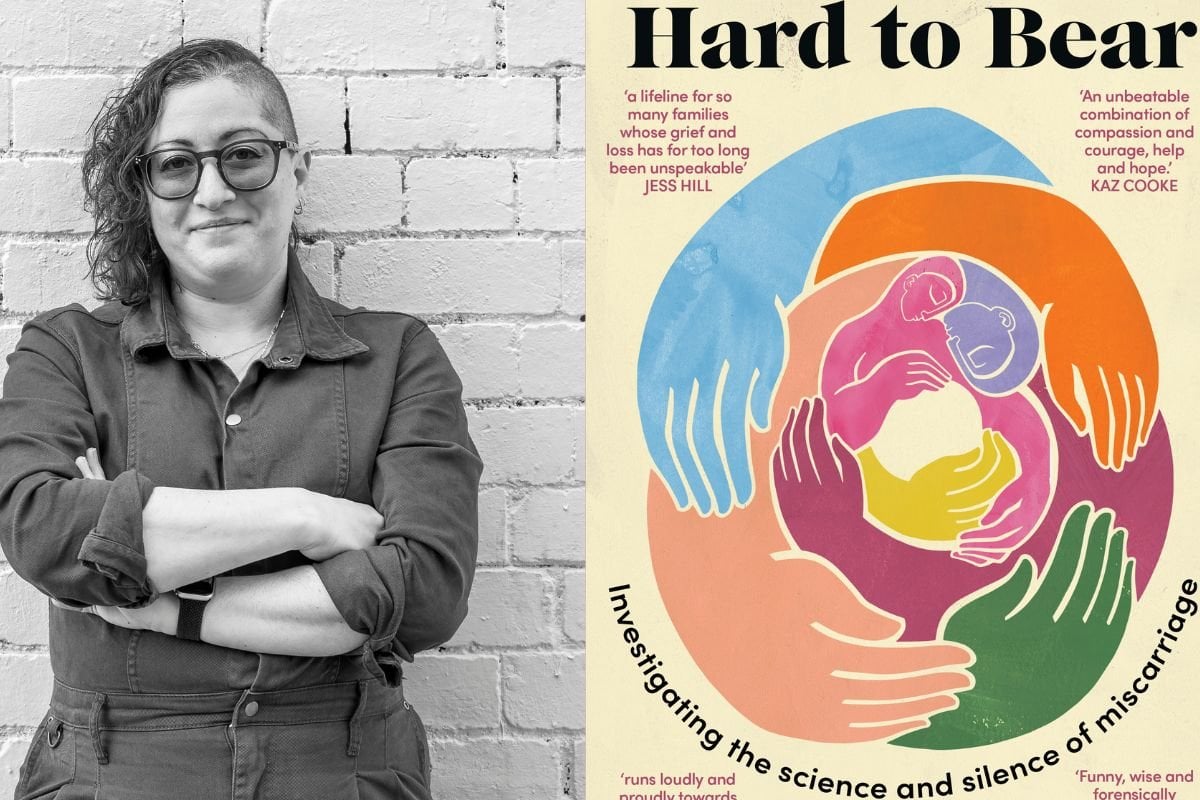

This is an edited extract from Hard to Bear by Isabelle Oderberg. Out now with Ultimo Press.

‘If women were educated about miscarriage in school, then this wouldn’t happen,’ the doctor said, gesturing towards me. All of me. ‘You’d know miscarriage was just a normal, natural thing that’s supposed to happen and you wouldn’t be crying about it.’

It was June 2018. I was in the middle of my sixth miscarriage, sitting in a chair, bleeding, cramping and sobbing into a tissue. I was in the office of one of Melbourne’s most pre-eminent obstetricians. A Cervical Celebrity.

As I walked out of his office, paid my bill and dragged myself towards my car, keeping my head down because my eyes were as puffy as campfire marshmallows, I had a moment of clarity, through the grief and the hormones.

This obstetrician spoke as a clinician who views a miscarriage solely through a scientific lens; a loss like mine was simply a chromosomally challenged cluster of cells, not compatible with life and requiring expulsion or removal. This man had delivered hundreds, possibly thousands, of babies and he was one of the best in the state, possibly the country.

But I also knew he’d never felt a baby move inside him; he’d never felt that magical connection, then lost it. A miscarriage is a full stop, when you want to keep reading.

Watch: Mia talks about feeling lost after miscarriage. Story continues after video.

Top Comments