"The disease has spread", his oncologist told us. "It's incurable."

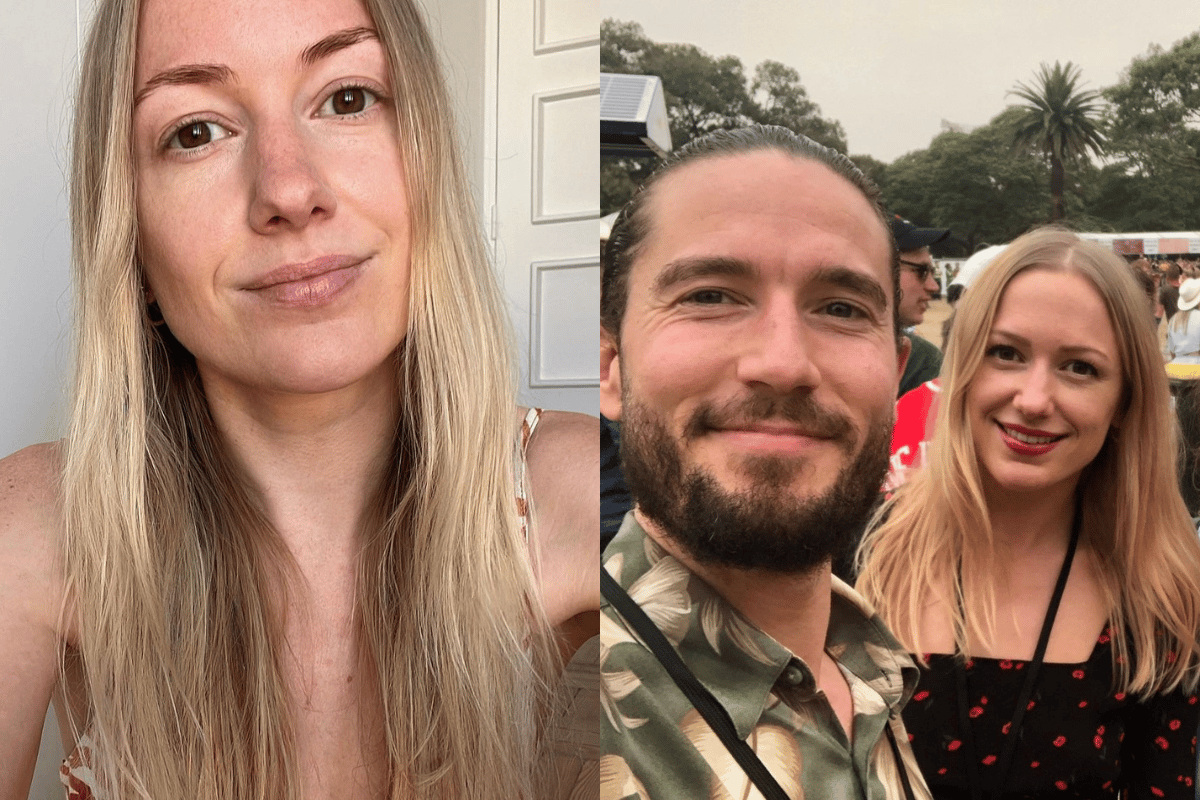

It was March 2020, two weeks into the first national lockdown at the height of the pandemic. My fiancé Ben had just been handed a death sentence at a cancer centre in London.

The malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumour that had been removed from his back the previous summer had metastasised. Now, there were lesions in both of his lungs.

In the weeks that followed the news, I swung between terror, panic and denial like a pendulum. We became prisoners in our own home, drowning in death tolls, oncology consultations and medical jargon, only leaving our flat to attend chemo and to walk the loop around our local park in a bid to conserve our sanity.

Watch: 5 things about grief no one tells you. Post continues below.

I was terrified of losing him. He was my best friend, my twin flame, my husband-to-be, the father of my future children. How would I go on living, I asked myself, in the absence of the person I knew I couldn't live without?

I wouldn't, I decided. He would be one of the lucky ones to defy the odds and beat it. Over the next seven months, we explored every treatment pathway possible — surgery, chemo, off-label drugs and genetic testing. Different diets, vegetable juices, medical cannabis and herbal supplements. Meditation, past life regression, hypnotherapy and counselling. But nothing helped him — not even the slightest bit.

Top Comments