Tina Gibson, 26, from Tennessee in the US has reportedly given birth to the oldest frozen embryo ever to come to term.

When Tina and her husband Benjamin couldn’t fall pregnant naturally, they decided to adopt a frozen embryo in March this year.

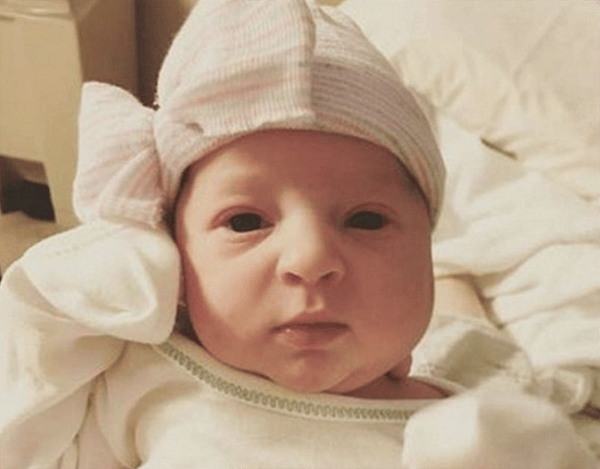

On November 25, baby Emma was born. She measured 20 inches long and weighed just under three kilograms, according to a statement from the National Embryo Donation Center in Knoxville.

Amazingly, the embryo that became Emma was conceived in 1992 – only a year after Tina herself was born in 1991.

The embryo was 24 years old at the time it was thawed and transferred in March.

Emma’s father Benjamin described his newborn as a “sweet miracle”.

“I think she looks pretty perfect to have been frozen all those years ago.”

Lab director Carol Sommerfelt said the birth of Emma was “deeply moving and highly rewarding”.

“I will always remember what the Gibsons said when presented with the picture of their embryos at the time of transfer,” Sommerfelt is quoted in the press release. “They said: ‘These embryos could have been my best friends’, as Tina herself was only 25 at the time of transfer.”

Top Comments

Fascinating story! After a lengthy process, my wife and I have finally been able to donate our 8 embryos (frozen in 2015). Initially we were a little unsure about whether to donate, but as we have friends who have major fertility problems, we soon realised that donating them would be an amazing gift to those individuals and couples. We are so stoked that 2018 could be the year that some of those little guys are born into the world!! If they choose to find us in 18 years (and meet their biological sister), that's great, but if we never meet them, we at least know they have been raised by people who will love them very much. I know it's a challenging idea for many but i'd 100% recommend donating your embryos if you have that choice.

I think embryo donation represents an area where the law is failing to keep up and it desperately needs to. To be honest, I think there are going to be a lot of kids down the line who are angry and confused about their origins - imagine finding out you were a donated embryo and that it was just chance and the doctor's decision that your particular embryo wasn't used by your biological parents and was instead leftover and eventually donated.

To me, the tone of this article talking about unused embryos as waste and suggesting that it's unfair to childless parents to have them unused reminds me of the attitudes in place when young unmarried mothers were forced to give up their babies at birth so that childless couples could adopt them. It was very much the same attitude of finding the supply of babies to meet the demands of childless couples and not at all about the interests of the babies or their birth families.