This week, Selena Gomez delivered a moving acceptance speech at the American Music Awards.

Referring to her battle with mental illness, she said “I was absolutely broken inside…If you are broken you do not have to stay broken.”

In August of this year, Gomez said in a statement to People magazine that she was taking some time off as she was suffering from “anxiety, panic attacks and depression”.

Listen to Mia Freedman, Monique Bowley and Jessie Stephens talk about Selena’s speech on Mamamia Out Loud:

My problem, however, is that when we only have privileged, thin, successful, and highly functional people sharing their struggles, we end up with a very skewed idea of what mental illness looks like. And when these people (Miranda Kerr as an example) offer advice on how to get better, we sometimes end up with very simplified, and often inaccurate, ideas of what recovery looks like.

It's not that we shouldn't listen to these people, or value their bravery for speaking openly about their experiences. It's that we should be aware that often, the people with the platform and the profile to speak about anxiety or depression are the exception, and not the rule, when it comes to mental illness.

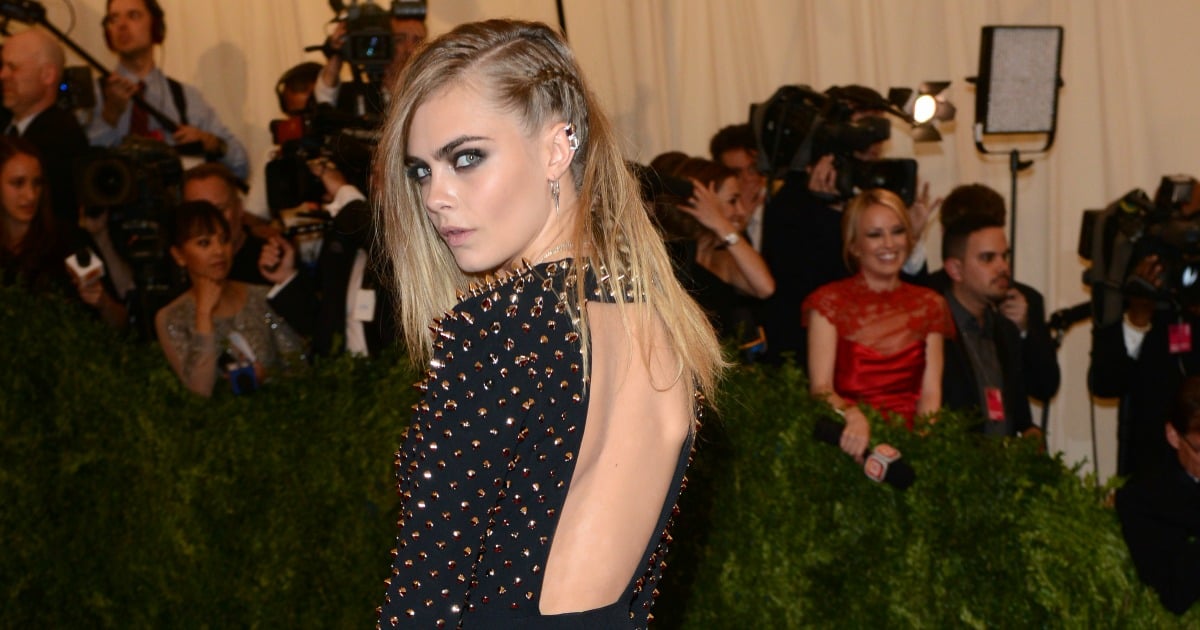

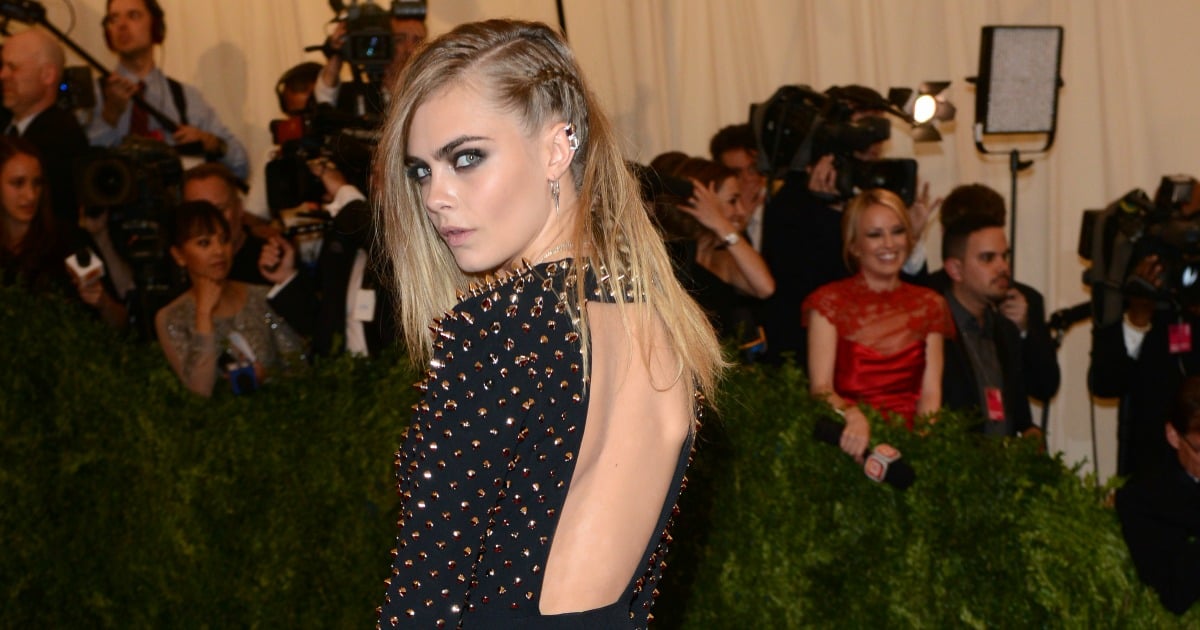

Because I can assure you, on the whole, anxiety doesn't look like Selena Gomez and Cara Delevigne. And it certainly doesn't look like either of these women on a red carpet or on screen.