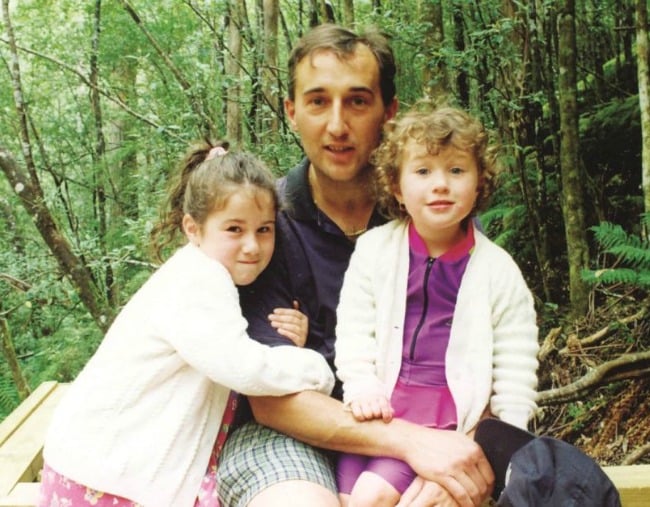

Twenty-two years ago to the day, on a Sunday, Walter Mikac was hosting a local golf tournament on the sprawling greens of a course in Tasmania. His wife, Nanette, and young daughters, Alannah, 6, and Madeline, 3, decided to visit the local historic site of Port Arthur as he played.

Standing on the golf course, Mikac remembers hearing shots flying from across the bay. They were coming from Port Arthur, he thought, but those on course assumed they were a re-enactment of sorts. Tasmania was a safe state, Nubeena — the place he, his wife and two young daughters had settled in, having bought the local pharmacy — a safer city. The family would rarely lock their doors at night.

When the game finished, he later wrote, a young couple ran into the clubhouse. People at Port Arthur had been shot, they yelled. Racing home, Mikac arrived to an empty house.

He would later learn Nanette, Alannah and Madeline had been killed by a lone gunman who shot 35 people and wounded 23 more.

He does his best not to think about that day.

“I don’t tend to look back at it, but it’s one of the main things that lives in your memory bank. So whilst it may not happen every day, and I may not re-live it all the time, there are certain days you feel emotional,” he tells Mamamia over the phone from his home in Byron Bay.

Top Comments

As a Tasmanian I can honestly say I have never, ever forgotten this family, or the other victims. I visit Port Arthur regularly and every time I drive past I remember. It is still raw after 22 years. I hope other Australians never forgot what happened that day and that we continue to be a society that is strong in its anti gun laws and values.

It’s nice how they trot out old Walter when they want to tug at heart strings, but can’t have a Coronial inquest due to the hurt feelings of the survivors.

Walter has first hand experience as to what it's like to lose his family to gun violence. I'd listen to him over you and you should show him more respect.

Really?

Walter lost his family to a lunatic and also to the Australian Govt failure to protect their people, nothing more.

No amount of law would have prevented this, yet the media love to dance on the graves of the innocent, over and over again, demonising something that has no bearing on a solution to the root causes of the problem.

Maybe you need to educate yourself a little more and grow up in the process.