On February 13, 2008, Australia’s then Prime Minister Kevin Rudd stood in front of parliament and apologised on behalf of the Australian government for the forced removals of Australian Indigenous children from their families.

“To the mothers and the fathers, the brothers and the sisters, for the breaking up of families and communities, we say sorry,” he said.

“And for the indignity and degradation thus inflicted on a proud people and a proud culture, we say sorry.”

Under government policies from 1910 to 1969, Indigenous children were removed from their families in an effort to be assimilated into ‘white Australia’. It’s estimated at least 100,000 children were removed, with siblings separated and irreparable damage done to Indigenous culture.

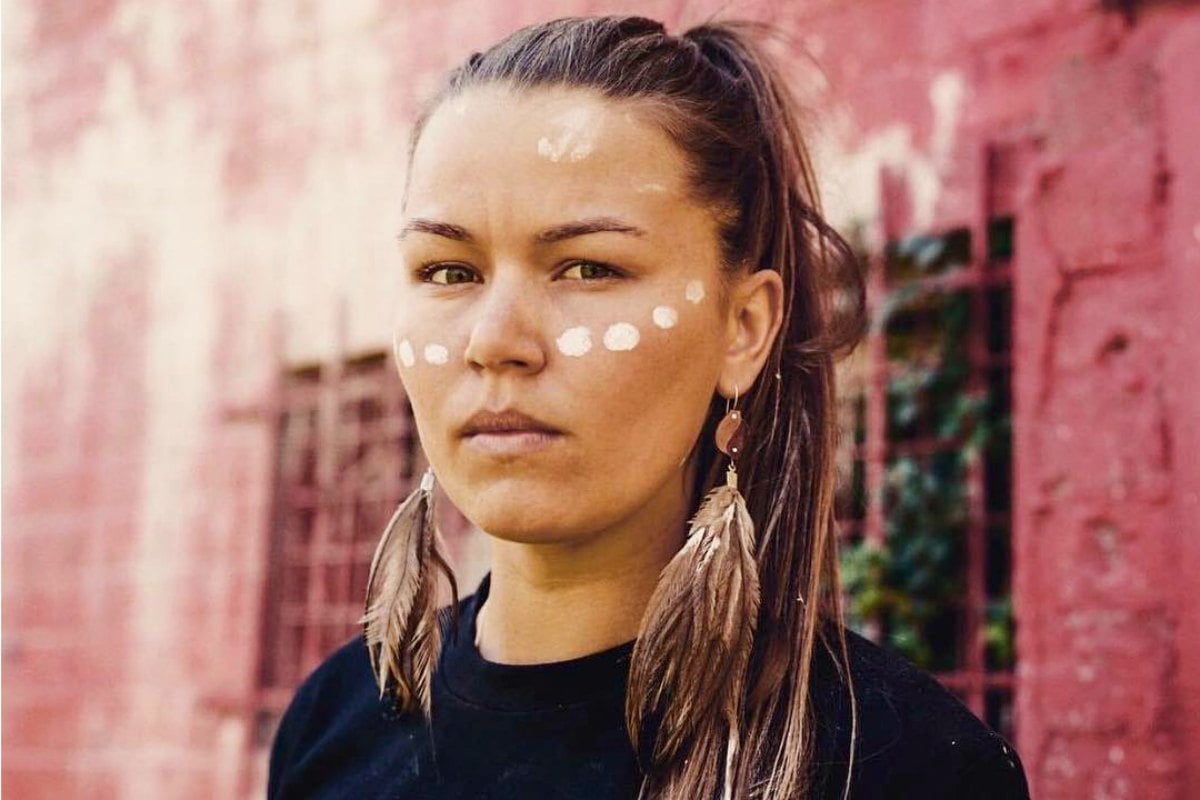

According to official records, this practice officially ended in 1969. But in the same year Kevin Rudd delivered his apology, 11-year-old Vanessa Turnbull Roberts was forcibly taken from her family and placed in out-of-home care.

View this post on Instagram

Top Comments

Wow, I'm so surprised with the volume of people saying that this Indigenous woman doesn't know a thing about her own experience. She knows better than anyone if she felt safe and happy with her family. She knows if she felt unsafe in some foster homes. That's her own experience. She's totally right that some things haven't changed. She's not even allowed to tell her personal narrative without non-Indigenous people telling her she's wrong.

Who's said that she doesn't know about her experience?

There are a few of people here talking about their own experiences.

Fair enough she knows what happened to her, but that doesn't automatically mean she knows whats best for everyone.

I was thinking this also. At 11 years old she was more then capable of understanding and advocating for her own choices and by ignoring them or condescendingly telling people that “it is for their own good” is not helpful. We need to listen to people’s lived experiences and take note.

There needs to be systematic change, with Indigenous leaders and elders leading it.

To be clear. Are you referring to systematic change in the Government or the Communities to manage and respond to these issues?