My bum is stuck to a green plastic garden chair and I’m crying.

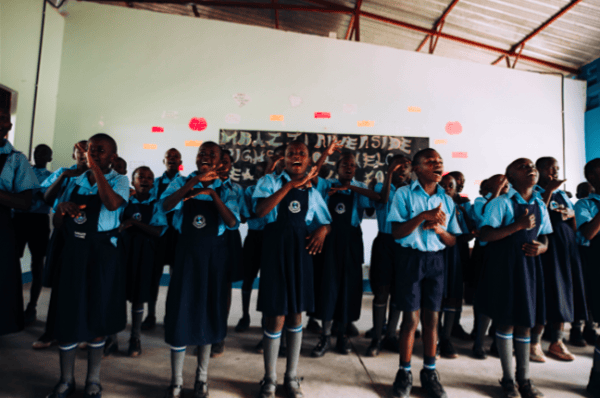

I’m 12,500 kilometres from home, listening to 100 Ugandan children singing the Australian national anthem. Our problematic lyrics feel, in the mouths of kids at a bush school in a patch of cleared jungle, like a dream, like a wish. Not a wish for these proud east-Africans to be Australian, but a wish for something many of us have – endless possibilities.

Next, a group of children stand up to sing a self-penned “thank you” song to this school and my tears come faster.

“I want to become a doctor, I want to become a teacher… Education changes everything…”

I look over at my nine-year-old daughter, Matilda, who is watching with saucer-eyes but dry cheeks. She sees me sobbing and gives me an encouraging smile. A tiny role-reversal.

Why are these Ugandan village children singing Advance Australia Fair? Because they’re welcoming a group of Aussie parents and kids to a school built by an Australian not-for-profit organisation called School For Life. And without it, their lives would be very different.

Top Comments

I think Uganda is doing a coverup of Ebola cases. That fellow whose family ran off with his corpse from the facility.. his symptoms sounded like Ebola. If that wasn't Ebola, I want to know what it was, not that I will believe the lie. Now there is wait on a 30yo fellow who got ill in a taxi and passed.

You couldn't pay me to travel to Uganda. .. well maybe if you paid me a huge amount and I could stay in fancy hotels.

I guess you didn't hear about that grandma that got kidnapped, either.

Yes because Australia is free of crime *eye roll*.

My cousin and husband live in Uganda and absolutely love it. I’m planning t family vacation there with my two little ones.

Tourists visitng Australia don't have to worry (generally) about being kidnapped and held for ransom, or a visit to a local market might expose you to Ebola (from those crossing over from Congo) or the worry about infection from HIV tainted blood products following a visit to the hospital. Yea, Uganda is certainly high on desirable countries to visit.

From the username, I suspect CaliforniaIsBeautiful is from the US, that other well-known crimefree country. I'm assuming they are also from California, a state that definitely didn't have a mass shooting literally yesterday.