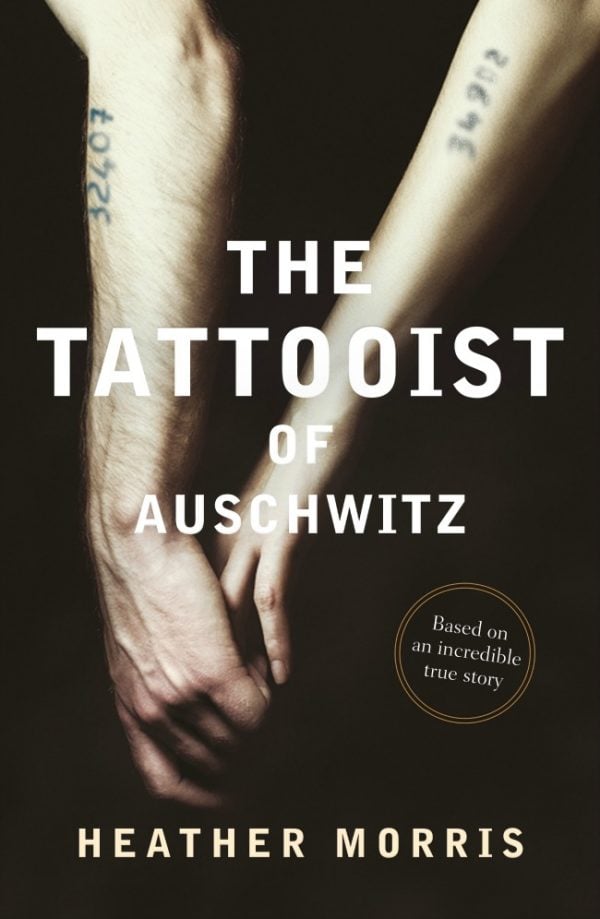

This is an edited extract from The Tattooist of Auschwitz by Heather Morris – a historical fiction novel that explores the real-life love story between Lale Sokolov and Gisela Fuhrmannova.

Lale tries not to look up. He reaches out to take the piece of paper being handed to him. He must transfer the five digits onto the girl who holds it. There is already a number there but it has faded. He pushes the needle into her left arm, making a three, trying to be gentle. Blood oozes. But the needle hasn’t gone deep enough and he has to trace the number again. She doesn’t flinch at the pain Lale knows he’s inflicting. They’ve been warned – say nothing, do nothing. He wipes away the blood and rubs green ink into the wound.

‘Hurry up!’ Pepan whispers.

Lale is taking too long. Tattooing the arms of men is one thing; defiling the bodies of young girls is horrifying. Glancing up, Lale sees a man in a white coat slowly walking up the row of girls. Every now and then he stops to inspect the face and body of a terrified young woman. Eventually he reaches Lale. While Lale holds the girl’s arm as gently as he can, the man takes her face in his hand and turns it roughly this way and that. Lale looks up into the frightened eyes. Her lips move in readiness to speak. Lale squeezes her arm tightly to stop her. She looks at him and he mouths, ‘Shh.’ The man in the white coat releases her face and walks away.

‘Well done,’ he whispers as he sets about tattooing the remaining four digits – 4 9 0 2. When he has finished, he holds on to her arm for a moment longer than necessary, looking again into her eyes. He forces a small smile. She returns a smaller one. Her eyes, however, dance before him. Looking into them his heart seems simultaneously to stop and begin beating for the first time, pounding, almost threatening to burst out of his chest. He looks down at the ground and it sways beneath him. Another piece of paper is thrust at him.