Last week, I wrote an article about Andrew Bolt.

As I was describing who he was, I included the sentence: Bolt denies there was ever a Stolen Generation (to be clear, there was).

I didn't give that sentence much thought. I just figured it was responsible to counter Bolt's opinion about the Stolen Generations with historical fact.

I received more emails in response to that sentence — or specifically the five words 'to be clear, there was' — than I have about anything I've ever written. The message was clear. There's no such thing as the Stolen Generations you lefty (bleep) why don't you (bleep, bleep) and look at the facts you ugly (bleep).

Up until this weekend, I was blissfully unaware that a debate still existed around the Stolen Generations.

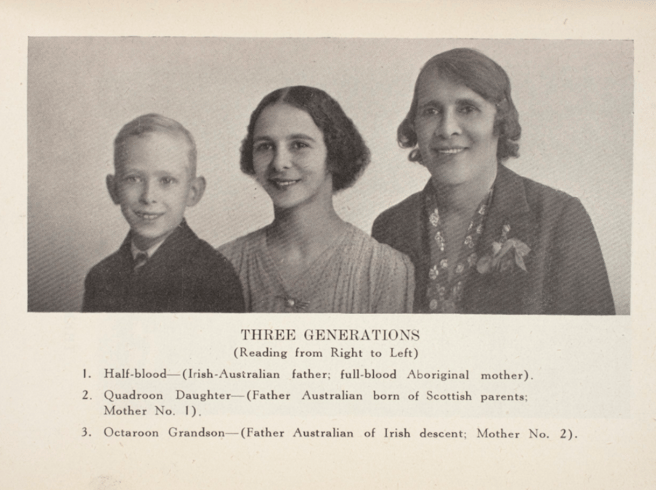

We have the Bringing Them Home report. It was published in 1997, the culmination of a national inquiry into the separation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children from their families. When it was presented to Federal Parliament, it was 680 pages long. There were no shades of grey. No ambiguities. The inquiry found that "Indigenous families and communities have endured gross violations of their human rights. These violations continue to affect Indigenous people's daily lives. They were an act of genocide, aimed at wiping out Indigenous families, communities, and cultures, vital to the precious and inalienable heritage of Australia."

It's interesting that there are features of history we do not deny.

Top Comments