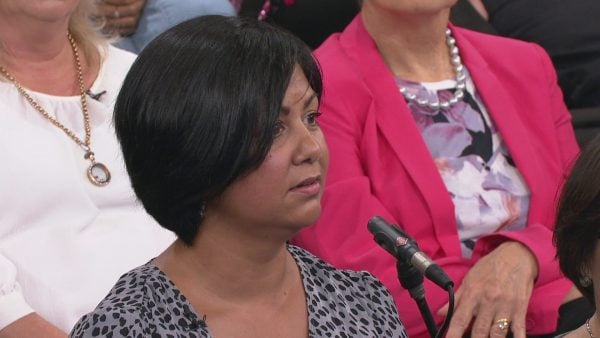

When I heard the rumour that my half brother was living with a woman who had two young children, I was filled with dread. Within a few hours, I was at the local police station to report the sexual violence I had endured at his hands for over 11 years. Little did I know of the roller-coaster ride I was embarking on.

Yet, if I had to do it all over again, I would. I was five years old when my innocence was stolen from me. His depravity wounded me profoundly. I was imprisoned for years in a cage of shame and silence.

The judicial process was a draining and frequently distressing experience. Even though I was quite naïve about the process, I had watched enough Law & Order episodes to know that I would be cross-examined. I respected and understood the need for the presumption of innocence.

I knew that it would be difficult and certainly unpleasant. The case was assigned to an amazing crown prosecutor whose demeanour was enough for me to assess that I was in good hands. We met sparingly, but she made great efforts in explaining each step of the process to me and of reassuring me that she would be there to support me. I was lucky to have her prosecute this case.

Top Comments

If people stopped falsely accusing people of things like this and DV, this poor woman's attacker would have gotten a much longer prison sentence and the trials would never have been dragged out.

The system is totally stacked against the victims in cases such as this. The legal process for sexual assault, especially that involving minors needs a total overhaul!!!