Today is the International Day of People with Disability. You can read more about it here.

This story was originally published in 2017.

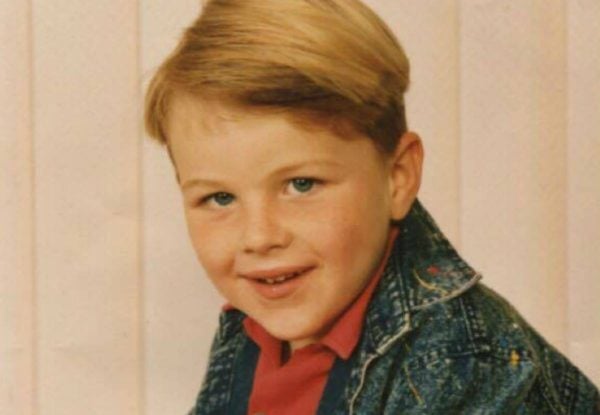

Simon has big blue eyes, a slightly lopsided smile and a tendency to rub his hands together rhythmically when he gets excited.

Simon is our cousin.

He was five years old when we were born and the three of us were in nappies at the same time. Dad still laughs about not being able to find nappies big enough to fit Simon, or small enough to fit Clare, who was a particularly tiny baby.

Gran would tell us Simon was “special”. He went to a “special school”. He was “a gift”.

And then we grew up and Simon… well, Simon didn’t. Not really.

As he got older, Simon’s job was to dress in a Santa costume on Christmas Day and give out presents. Sometimes he did a puppet show, or told a joke that didn’t entirely make sense, which made it even funnier. We always laughed with him not at him. He has always held a special place in our extended family.

As an adult, now 33, Simon has fallen in love with musicals and spends many of his days riding trains all over Sydney. Simon is kind, funny and asks more questions than anyone you’ve ever met. He’s also honest, except when it comes to the question of; “have you had lunch yet?” in which case the answer is always “no,” even if he has, in fact, eaten lunch. Three times.

Top Comments

So beautifully written! This topic is always going to bring controversy, but I feel it is better to talk about it and start a conversation then to not.

Thank you for sharing such a personal story, Clare and Jesse: although I continue to be confused as to how an article dated today, December 3rd 2018, can have comments from a year and 2 years ago. Is it something you update every year in the lead up to the International Day of People With Disability?