It’s a strange feeling to hold all the memories of your family. To have no one left to corroborate childhood memories with. To know gaps in your knowledge will never be filled. What was your first food? How did your parents meet? What was their favourite food?

My mum died 19 years ago. My dad only months. As an only child, there is a particular weight to being the only family member left.

Here is what I have learned.

You cannot grieve in advance.

Grief comes after the death. Or at least another form of it. Knowing the Grim Reaper is hovering nearby unleashes a certain type of mourning. A knowing that things are set to change irrevocably. Even though you know a loss is coming, you cannot prepare for it. You can’t cheat.

My mum was unwell for years. A horrible tumour on her brain stem that just wouldn’t f**k off.

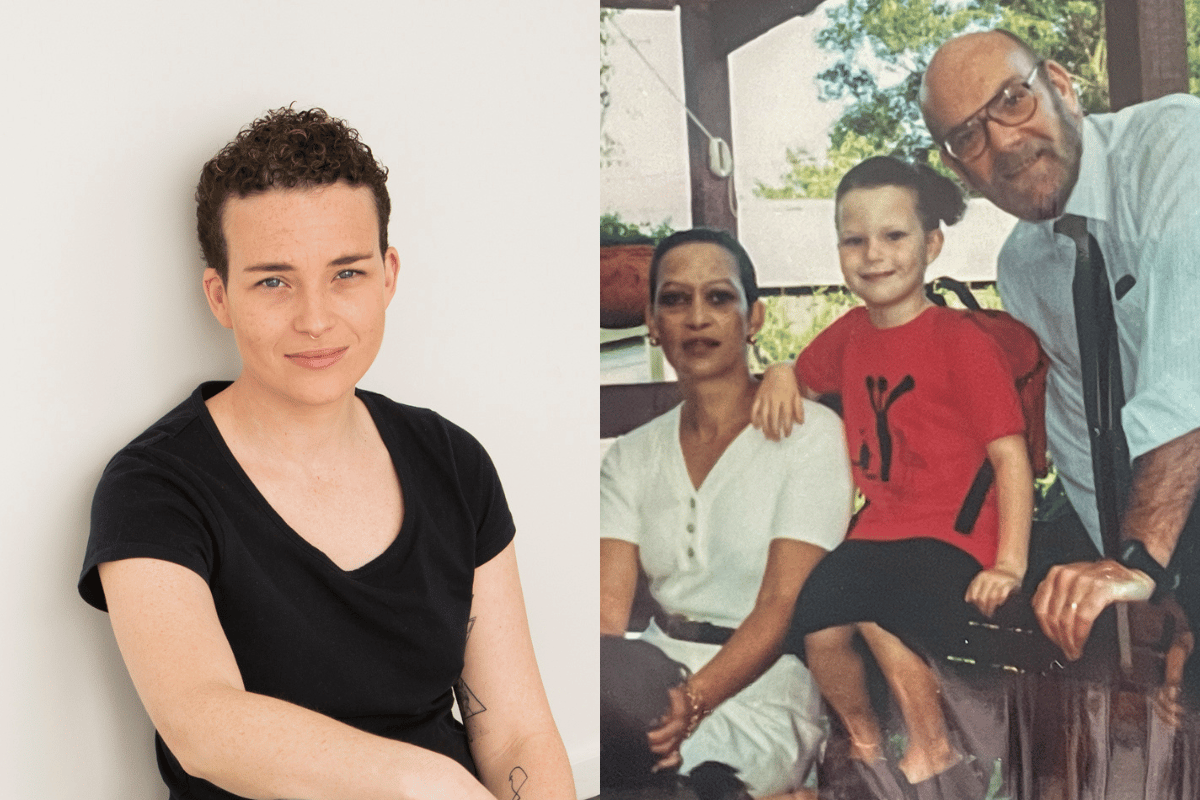

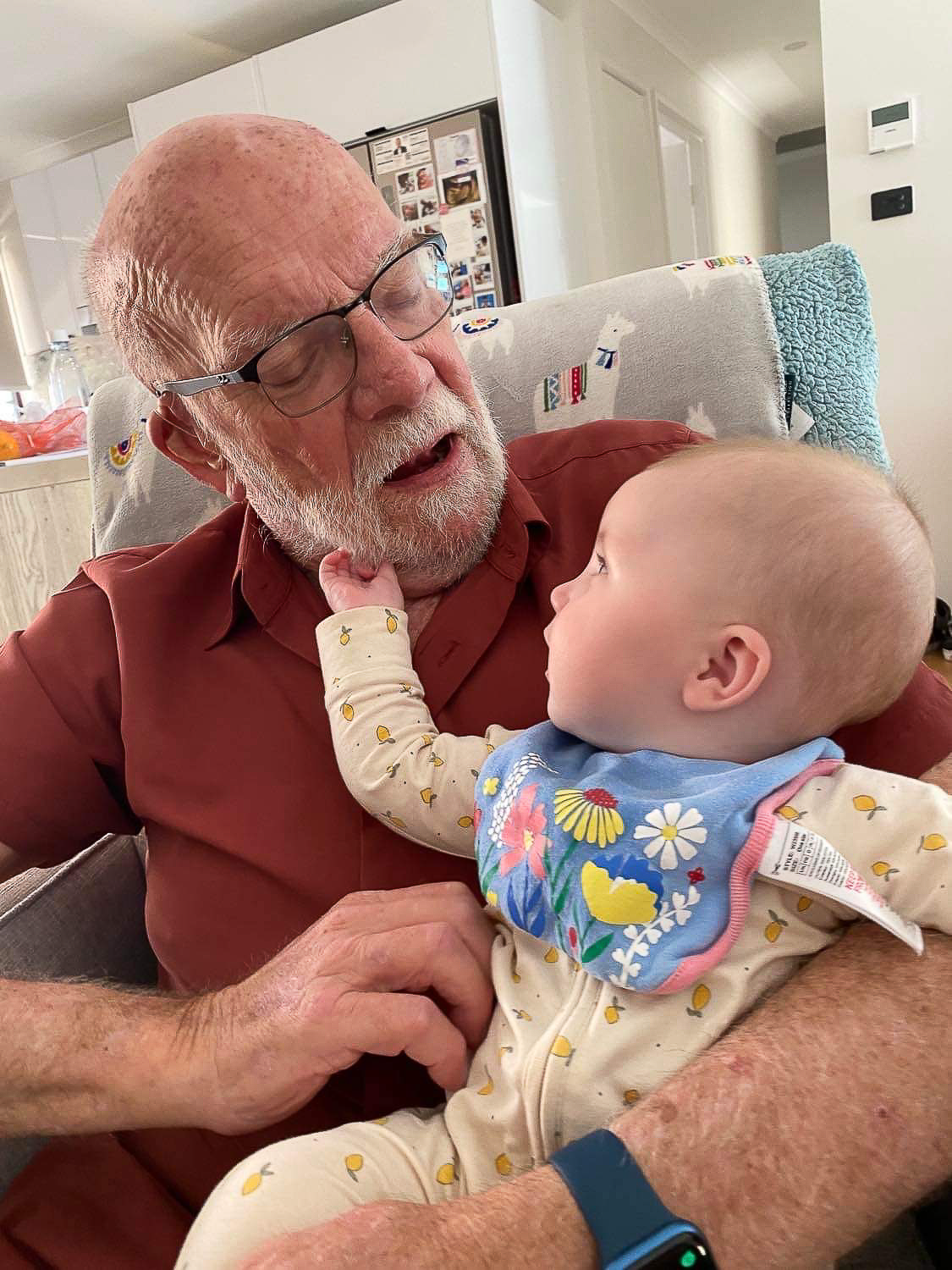

Image: Supplied.

Image: Supplied.It wasn’t cancerous, but these raspberry-like bubbles of blood gathered on arguably the most crucial part of the body and couldn’t be left unattended.

The first surgery was a shock, but Mum mostly recovered - a bit of bodily numbness and a limp. Lots of rehab and physio, but she continued lecturing fashion and education at the University of Canberra. Continued driving her red convertible sports car.

Top Comments