Joan Atherton Hooper is about to open the case files for her father’s murder in 1939. The files have been closed for 75 years – most of Joan’s life – but after being reopened to the public in January, she is finally able to challenge her own suspicions about the murder.

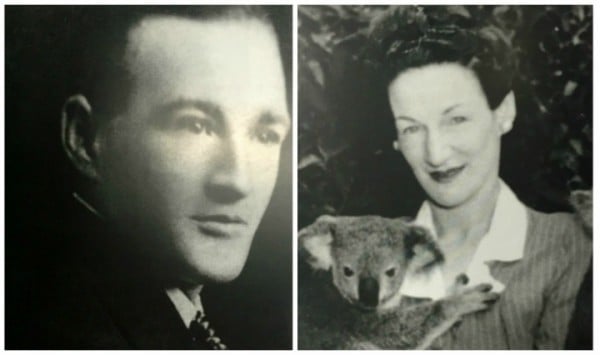

Alfred Atherton was 35 when his wife’s secret lover shot him dead in Ferntree Gully, in Melbourne’s outer east. This much Joan knows from newspaper archives she has read.

But the circumstances around the murder are contested, and Joan has always had her own questions.

The biggest of all: was the killer acting alone, or was her mother behind the murder as part of a bid for freedom from her husband?

What Joan knows so far

The Atherton family was in disarray when Alfred was killed. Joan and her four older siblings had been sent to an orphanage because their father was not able to care for them while working full-time.

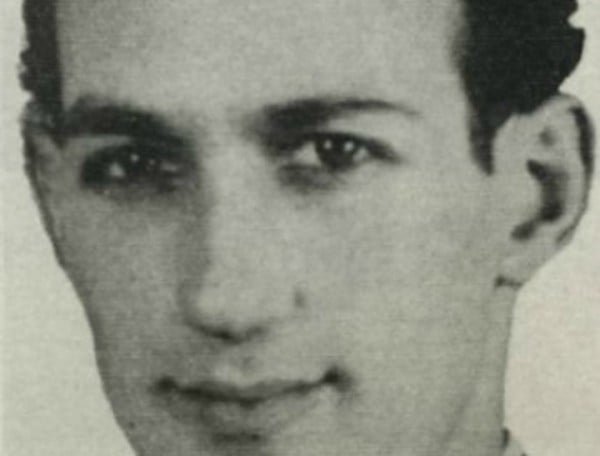

Their mother, Dorothy, had disappeared. It was not the first occasion, but this time she was staying with her young lover, 19-year-old Morris Ansell.

And she was pregnant with his child.

In 1939, women in Victoria did not have the right to divorce their husbands, so the only way for Ansell and Dorothy to be together was if Alfred granted Dorothy a divorce, and that was not on the cards.

So Ansell found another way to remove Alfred from the equation.

He approached Alfred promising he knew where Dorothy and the children were, and that he could take Alfred to meet them in Ferntree Gully.

"Because our father didn't know the part Morris Ansell played in our mother's life, he went with [Ansell] unwittingly to Ferntree Gully," Joan said.

After getting off the train together and walking a short distance down a dirt track, Ansell pulled a rifle out from under his coat and shot Alfred.

Ansell then went to call a taxi back to Melbourne, leaving Alfred to die in a pool of blood - his pockets filled with Christmas presents he had brought for his five children.

Meanwhile, Dorothy was at a cinema in Coburg with friends, and returned to bed with Ansell later that night.

"The lurid details made for great reading - every city and every main newspaper had it as their headlines," Joan said.

Dorothy's alibi cleared her of any direct link to the murder, but Joan and her daughter Karen remain curious as to what knowledge Dorothy had of Ansell's plans.

"What happened between her [Dorothy] and Ansell, we may never know," Karen said.

A death sentence and a disappearance

After police traced the rifle back to Ansell and prosecuted him for Alfred's murder, he was sentenced to death.

A jury sought compassion for him because of his young age, and his sentence was transferred to life imprisonment.

Throughout the trial though, Dorothy's character was brought into question, with police describing her as a woman of low morality and "really a bad type of woman".

"Gradually she took charge of him and playing on his feelings and his vanity," the Inspector General wrote of Dorothy and Ansell.

After Ansell was imprisoned, Dorothy was not allowed to visit him in jail.

Six months pregnant, publicly shamed and having lost both her husband and her lover, she disappeared again, this time not to emerge until many decades later.

As Joan prepared to examine her father's case file in February, she explained her theory for her father's murder.

"My opinion is because of the age difference, and my mother's background, I actually feel a modicum of sympathy for Morris... he doesn't look like a murderer," she said.

Joan believed her mother used her age and prowess to manipulate the love-struck man, 12 years her junior.

"I blame my mother more [than Morris]," she said.

Looking for clues in a 75-year-old file

Public Records Office of Victoria archivist Jack Martin takes Joan and her daughter Karen to a room to view the murder file.

"The more I know about my mother's involvement, the more it'll be clearer to me what her side of the story is and what transpired exactly," Joan says.

"I'm expecting that I'll have a reaction but which reaction I don't know, because emotions are funny things."

Mr Martin offers Joan a thick manila folder with about 40 pages inside - psychologists reports, witness statements, police interviews and court transcripts.

He explains the files have been closed for 75 years because to protect the privacy of individuals involved in the case who may still be alive.

"After 75 years, when the case involves adults, most people will be very old or deceased by the time they're opened," he says.

After only a few minutes of reading, Joan stops, aghast.

"I'm just astounded at something I've just read," she says.

A Victoria Police report describing Ansell has caught her attention. Instead of painting a picture of the impressionable young man Joan had imagined, a darker character is observed.

"The prisoner has been a very wayward youth and apparently could not be controlled at home," the report reads.

"He first came under notice of police when he was 14 years old. He was then charged with larceny...convicted and placed on 12 months' probation."

The report goes on to describe a violent assault on an elderly woman, and signs of a violent temper and dangerous moods.

Joan sits back in shock.

"I saw this young man as being this guileless youth who fell under my mother's influence because she was 32 and he was 19," she says.

"I've always thought she was behind my father's murder."

On another page, a medical report describes Ansell in similarly disturbing terms.

It says Ansell was completely infatuated with Dorothy, perhaps partly because she was the first person he had been intimate with, according to his own admission.

"He admits that he wanted to marry her and that he resented her husband's 'dog in the manger' attitude'," the report reads.

"He does not seem to experience the slightest remorse for his crime."

Skeletons in the closet

Joan is not the only person who has searched for answers about this dark episode in her family's past.

In Queensland, 54-year-old Rodney Lovell spent many years on what he described as an obsessive exploration of his family's history.

There was one uncle he was always curious about - a "gentle man" who lived in New Zealand when Mr Lovell was a child: Ansell.

"He was the one in the family who wasn't spoken about much," Mr Lovell said.

"I remember sharing a room with Morris' son and Morris would come in and give his son a kiss on the cheek and he'd give me a kiss on the cheek."

Despite being sentenced to life in prison, Ansell was released after 15 years and he went on to start a new life and a family of his own.

After Ansell died, Mr Lovell searched newspapers archives and found out about Ansell's darker past.

"It was a total shock - it did not compute he would be capable of murder," Mr Lovell said.

Dorothy was not able to hide the skeletons in her closet forever either.

The child she bore to Ansell grew up unaware of her five half-siblings, including Joan, until she married and started doing her own ancestry research.

Shocked by what she discovered, she tracked down Joan and offered to take her to Dorothy at a public housing flat in Williamstown, where Dorothy was living.

"It was unbelievable how disinterested she was, and she'd seen her daughter for the first time," Joan said, recalling the meeting.

Sitting at the Public Records Office reflecting on what she learnt about her mother and Ansell through the files, Joan said she had gained little sympathy for her mother.

"Years ago, I cried as a child with my head in a pillow wishing my mother would come and get me," she said.

"I'd been through a gamut of emotions throughout my life.

"But knowing the history of her I now know, and however hard my childhood may have been, I still think I was lucky I didn't go with her."

Joan Atherton Hooper has documented her story in length, in her autobiography Nothing to Cry About.