Content warning: This story includes depictions of violence and sexual assault that may be distressing to some readers.

When Lucie Blackman went missing in Tokyo Japan, it soon sparked a massive manhunt and media frenzy, Japanese police determined to find out what had happened to the young woman.

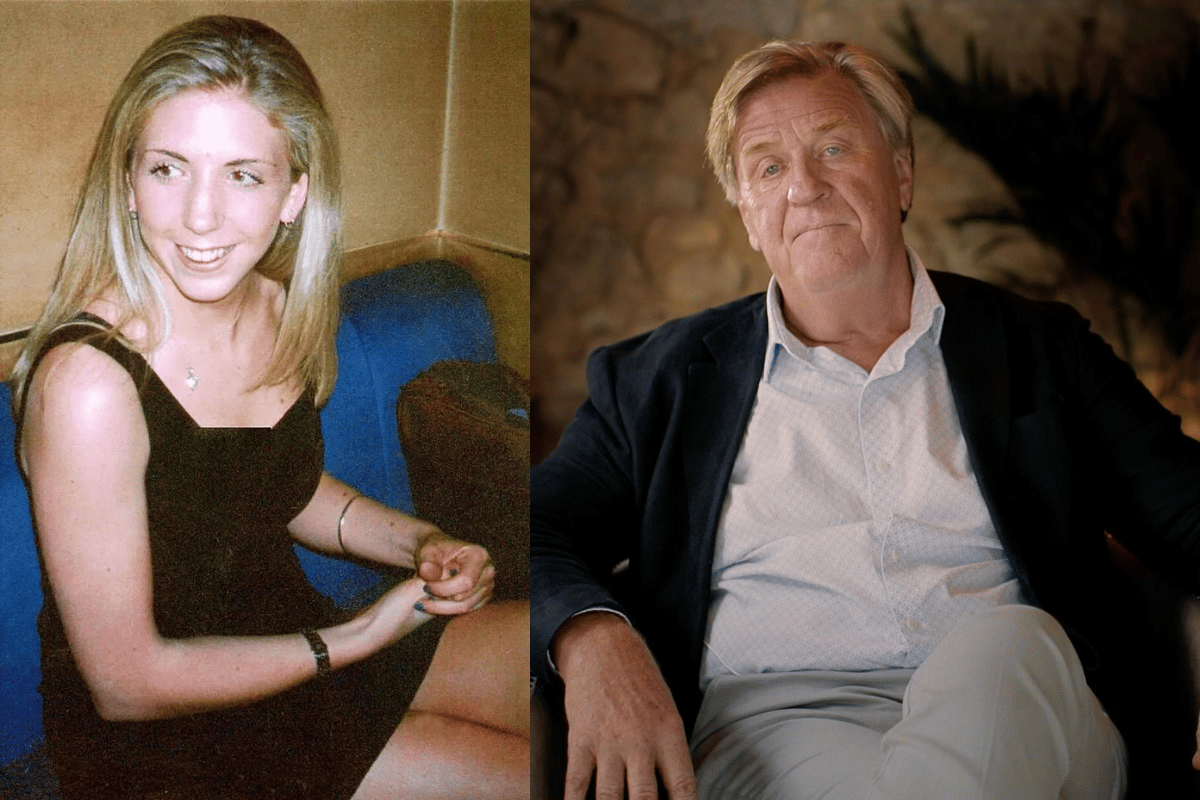

Lucie - a 21-year-old British tourist - disappeared on July 1, 2000, the case unpacked in Netflix's new true crime documentary, Missing: The Lucie Blackman Case.

When Tim Blackman received the phone call to say his daughter had gone missing, he didn't believe it.

Lucie had been working over in Tokyo as part of her plans to travel around Asia. She had left behind her job as a flight attendant and was working in hostessing at a venue called Casablanca in Roppongi, Tokyo.

Watch archival footage of Japanese police handing out missing posters on Lucie Blackman. Post continues below.

In the Netflix documentary, it was explained that there isn't much of a Western equivalent to the job of being a hostess in Japan. Essentially, a hostess club is a sort of nightclub that employs predominantly female staff to cater to wealthy men seeking drinks and attentive conversation. There is a strict no-touching policy.