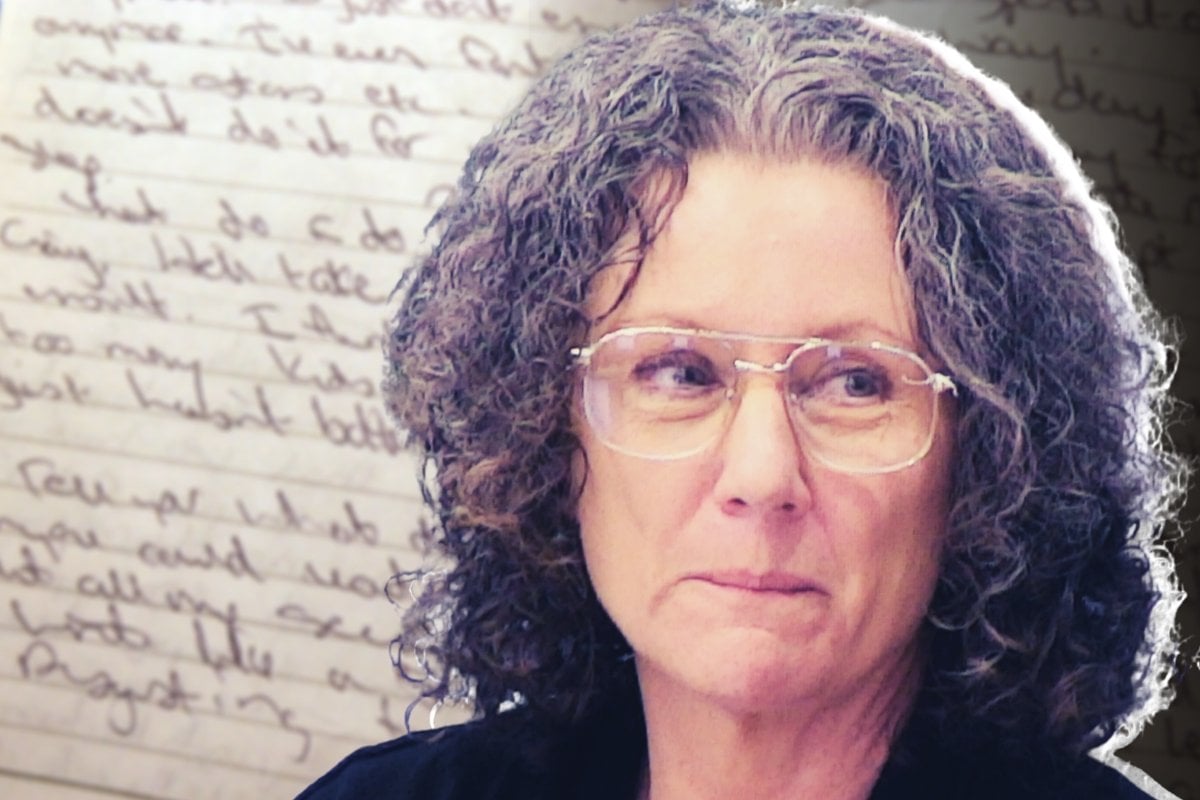

Kathleen Folbigg's life is one scarred by death. It's the reason Australians know her name. It's why she spent 20 years in prison and was once - incorrectly - dubbed "Australia's worst female serial killer".

Yesterday, Folbigg was pardoned and immediately freed from prison after a report from NSW chief justice Tom Bathurst KC on Friday stating that there is "reasonable double as to Ms Folbigg's guilt".

But nothing will make up for the years she has suffered behind bars - or the difficult and dark family history that is an integral part of her story.

Between 1989 and 1999, the NSW woman gave birth to four children, none of whom lived to see their second birthday.

The tragedies were first attributed to natural causes including Sudden Infant Death Syndrome and epilepsy. But in 2003, a jury determined beyond reasonable doubt that Kathleen Folbigg was guilty of murder, accepting the Crown's case that she smothered her children in fits of frustration and resentment.

For years, that verdict was called into question. In 2021, a collective of 90 leading scientists, including two Nobel laureates, signed a petition to the NSW Governor pointing to recent medical and scientific discoveries that cast doubt over Folbigg's guilt.

And finally, yesterday, Folbigg was pardoned and freed.

Throughout the coverage of this enduring case, a story has emerged of a complicated life, one that was scarred by yet another death years earlier; a death that not even Kathleen Folbigg knew about until she was a teenager.

Listen to journalist Jane Hansen's full conversation with Mia Freedman about Kathleen Folbigg's life and crimes on No Filter. Post continues after.

Top Comments