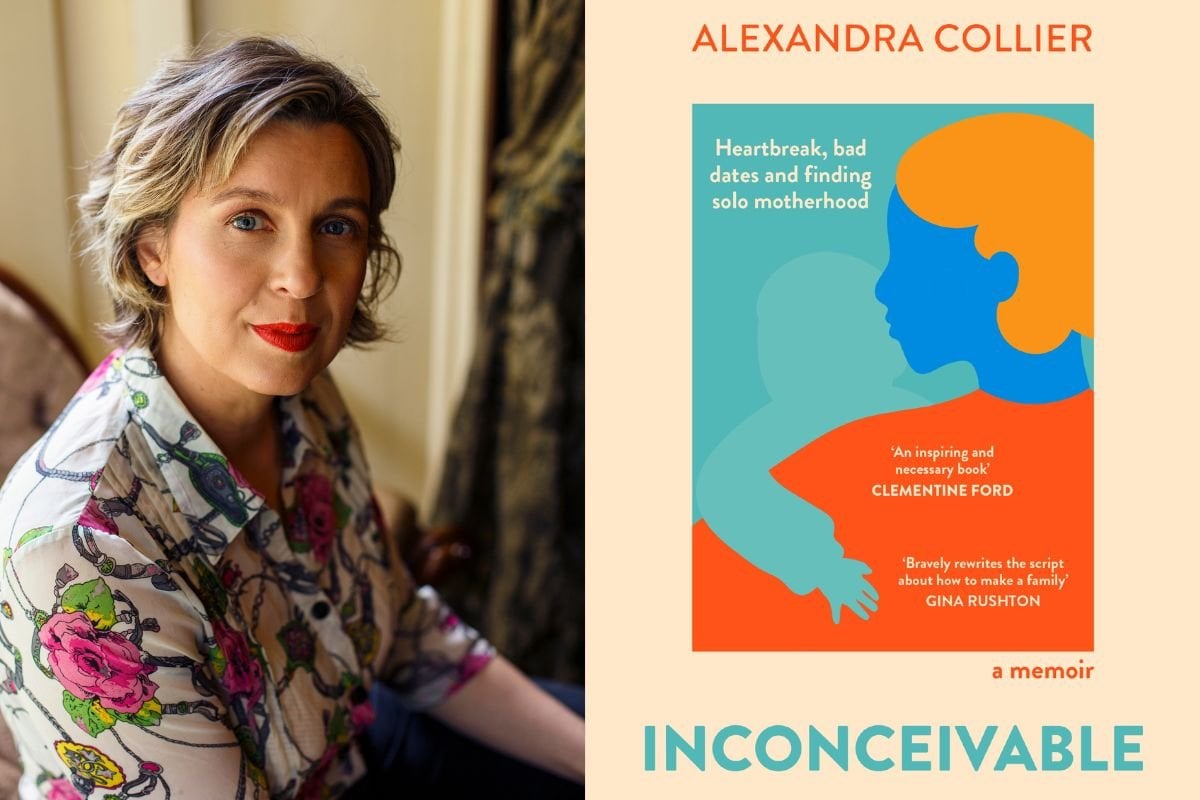

This is an edited extract from Inconceivable by Alexandra Collier published by Hachette, available now.

In the lead-up to Christmas, just before I started fertility treatment, I went to the acupuncturist, I jogged, I trained at the gym. I meditated. I felt like my body had become a thing to be tuned and trained and constantly improved upon.

I went to a wildcrafter – a kind of naturopath-cum-witch. ‘To be a mother, you need to learn how to mother yourself,’ the wildcrafter told me in her gentle Canadian accent. I wondered how to do that exactly.

‘Your womb is a garden,’ she explained. ‘You’ve left it quite late to tend the garden but we’ll do our best.’

The wildcrafter mixed me up a sludgy brew of herbs for my womb garden that tasted like a dredged pond. As I drove home, I tried to visualise my womb, but I could only picture a rubbish heap full of weeds.

At night, before bed, I wrote letters in my journal to my yet- to-be-conceived child. You will not be deterred by all this talk, I wrote. You will stick and grow. You will be mine and I will be yours. I can’t wait.

Watch: Meshel Laurie shares what it's like to go through IVF alone. Story continues after video.

Then a few days later: There is no knowing if it will work and if it does, what terror and joy may follow.