"We have all felt that uncanny sensation that someone is watching us. We can’t see them, but we feel something over our shoulder, their intense gaze. It’s as if their eyes are sending out tiny, tangible sparks of light, which tickle or singe our skin.

"To be physically different is to be continually assailed by these missiles of looking. Those of us who are stareable absorb these sparks into our bodies. We carry burn marks and develop scar tissue. We are tense, bracing ourselves for unwanted attention. We doubt ourselves, our beauty. These fires disable. They can even spread out beyond the hearth to burn others. At the same time, harnessed, they can warm and sustain." — Andy Jackson, Growing Up Disabled in Australia.

***

To young Carly Findlay, disability had a particular look. It looked like people in a wheelchair. It looked like Paralympians, or the people sharing their 'inspirational' story on the telly. It looked like her classmate with cerebral palsy, who spoke differently to her, moved differently to her, and was treated differently by teachers and her family.

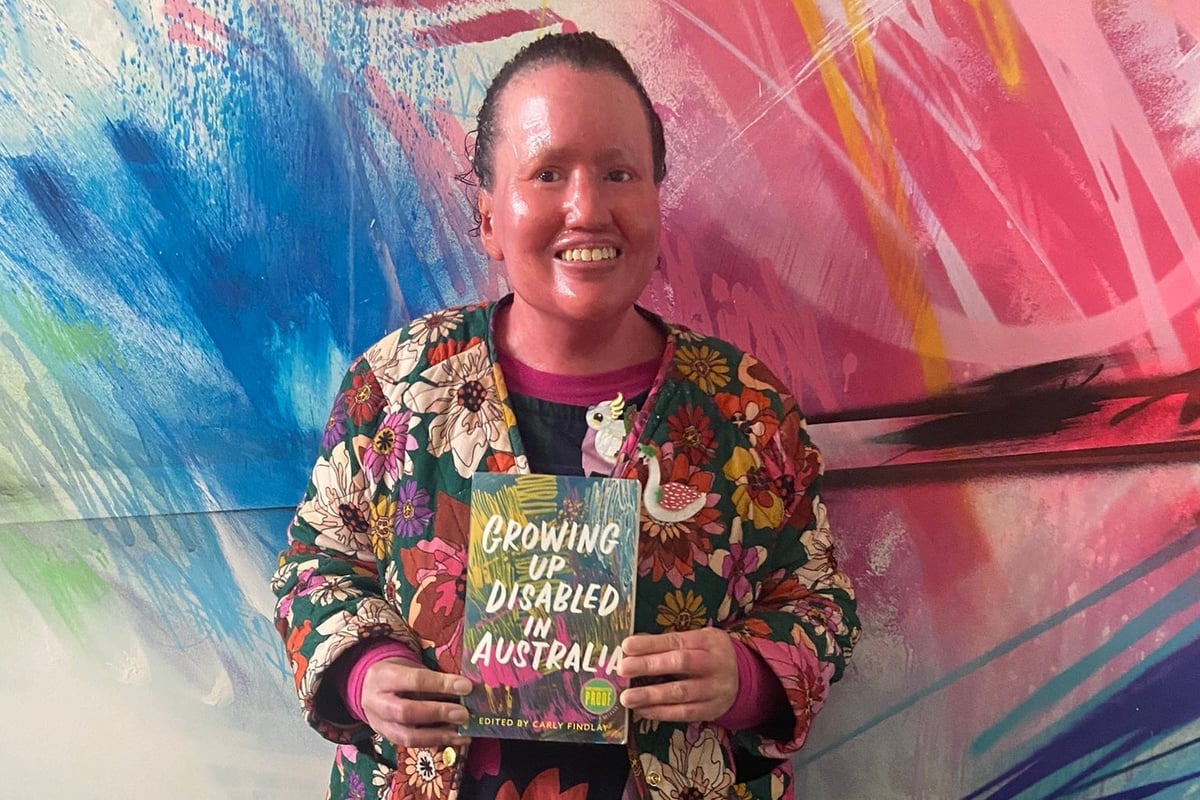

It wasn't until Findlay was in her 20s, when she mentored children with a chronic illness, that she saw herself in that image. She too had a lifelong condition (a rare skin condition called ichthyosis), she too had hospital stays and days off school, she too experienced marginalisation and discrimination. She too is chronically ill, she too is disabled.

"If you don't call yourself disabled, if you reject that term, you don't know how to ask for what you need," the author and advocate told Mamamia. "And so the disabled person in my school year got the help she needed, but because I didn't see myself like her, I didn't ask."