I was 15 years old when my mum sat tearful in my nan’s kitchen and told me that the man I’d called ‘Dad’ my entire life wasn’t really my biological father. The words hung in the air, indigestible.

My nan jumped up to pop the kettle on. Peak Britain, right there. Nothing that can’t be fixed with a nice cup of tea.

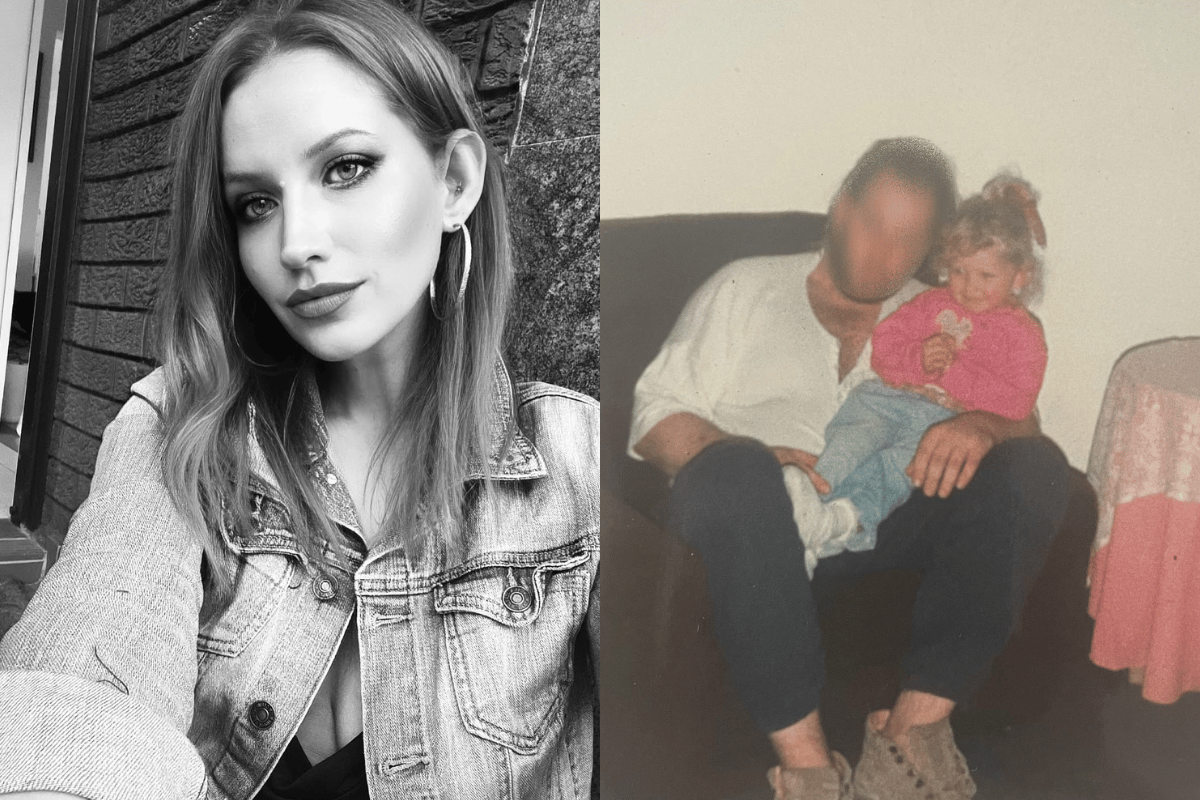

I couldn’t tell you the exact details of what I said, or how I felt immediately after. A psychologist would probably have an eloquent explanation, but I find a lot of my childhood memories slip away as I go to grab them, the way colour fades from a picture.

That, or I remember something as though I observed it from afar. Like watching a movie of my own life - a passive viewer, quietly accessing traumatic experiences from a more comfortable place. It’s not a ‘normal’ way to recall things. It feels like a perspective I shouldn’t have. So I second guess my 'memories' a lot. Perhaps they were just nightmares.

Watch: Mary Coustas on the pain of losing her father. Post continues below.

At some point, though, I settled on feelings of vindication and relief. My entire childhood never felt quite right, but I couldn’t put my finger on why. I just had this sense that things didn’t fit together the way they should, and at last, it all made sense.