Erin was sitting in a doctor’s surgery with her mum waiting on the results of two pregnancy tests. She was 14-years-old.

Her stomach was hardened and protruding so much that her mother, her doctor, and even Erin herself to some extent, believed that she must be pregnant. She vividly remembers the way that her stomach bulged.

“I remember laying down and I used to hit my lower belly to be like, ‘Why can’t I get rid of it?’” She tells Mia Freedman on Mamamia’s No Filter podcast. “And then I used to push on it and see what it would look like with a flat stomach.”

Pressing down on her belly didn’t necessarily hurt, but she had started having cramped feelings in her stomach – a feeling that, up until this point, she had assumed was normal.

The pregnancy tests came back negative. But any relief only lasted until the results of her scans arrived: an enormous cyst had grown in Erin’s lower abdomen.

Surgery was scheduled immediately to have the cyst removed.

“I was cut from hip to hip, like a Caesarean. And they said they had to drain it and it was about three kilos, almost a few litres of fluid before they even got anything out.”

The cyst led to Erin’s diagnosis with polycystic ovary syndrome (or PCOS), a hormonal condition that causes enlargement of the ovaries and the growth of cysts on them. The condition is also associated with issues like irregular menstrual cycles, excessive facial and body hair, acne, weight gain, reduced fertility, and an increased risk of diabetes.

PCOS runs in Erin’s family and she recalls how the extreme pain of menstrual cycles was fairly normal in her household as she was growing up.

“My sisters and mum, they were always on the floor with a lot of pain with their period,” she says.

As a teen, Erin would be forced to endure ours of agony and abnormally heavy bleeds that required her to change pads every hour.

“My mum used to say, ‘That’s normal. Your sisters do that, I have to too.’”

In the years after her first surgery, Erin describes that she had a “snowball effect” of cyst growth and surgeries.

Often, women who grow ovarian cysts will find that they go away without treatment. However, in Erin’s case, the cysts would not resolve themselves quietly, instead, they would rupture – violently.

“It feels like you’ve been stabbed or someone’s pouring boiling hot water inside your uterus. It’s excruciating. And it comes on so quickly. Like, you could be making dinner, laying in bed and you don’t even know what’s triggered it.

But when it happens, it’s like you can pass out from the pain and I’ve been almost at the brink of passing out.”

While Erin was battling with the symptoms of PCOS, she was also living with another condition that went largely ignored until her late teens: endometriosis.

Endometriosis is a condition in which some of the cells similar to those that line the uterus (otherwise known as the endometrium) grow in other parts of the body. It’s a chronic condition that affects about one in nine Australian women by their 40s and it causes tens of thousands of hospitalisations every year.

Erin says that the sensation of endometriosis pain is hard to describe.

“It’s just like a burning, stabbing, stretching feeling… like your belly is swollen from this cramping, it just feels like a balloon and it feels like your body can’t possibly push out your stomach anymore.”

Life quickly became a blur of intense pain, surgeries, and shorter and shorter periods of recovery. She started to feel socially isolated as all the things her friends were doing in their teens and early 20s – holidays, parties, dating – became impossible for Erin. Her symptoms were simply too severe.

On top of this, Erin carried the financial burden of her conditions.

She says that she’s paid over $30,000 for the 17 surgeries that she’s undergone, including four in 2019 alone. She believes she’s spent more time in and out of the hospital than she has at birthday parties or at the beach.

Erin’s career has also suffered – although this would be difficult to guess if you were watching her on TV.

Erin first appeared on Australia’s reality TV circuit back in 2018 as a contestant on season one of Love Island Australia. In 2020, she featured on I’m A Celebrity… Get Me Out Of Here! However, behind the scenes of both of these shows, Erin was battling with PCOS and endometriosis.

On Love Island, where contestants are frequently filmed in swimwear and revealing clothing, she resorted to extreme methods to make sure her issues weren’t made visible.

“I would wear a tampon 24/7 on Love Island, literally 24/7. Because I knew that I had really bad periods, even though I was on the Pill, I would still bleed through sometimes and I didn’t notice.

So I would wear tampons, even if I wasn’t bleeding… to pull out a dry tampon is so painful – but I was like, ‘That’s worth it’. Because you’re in bathers all the time or you’re in the pool.”

And while Erin downplayed the severity of her conditions to the producers of both shows, she says things got far worse when she entered the jungle to shoot I’m A Celebrity.

“I actually had a blood clot come out of me while we were walking back from one of the trials and it went all down my leg, it ruined my shorts, like it burst. I remember I grabbed it from my shorts and I kind of threw it… and Ryan [Gallagher] and Myf [Warhurst] were there – and Darren, one of the producers.

I was like ‘Oh my god’ and I just remember all this blood on my hand… I had to take my shorts off to give to [the producers] to clean properly.”

The stress and deep frustrations caused by her PCOS and endometriosis culminated in the feeling that, at 23-years-old, she just wanted to rid herself of all the burdens of her conditions.

She wanted it “all out” and started looking into the possibility of having a hysterectomy – but she was shocked by the resistance that she was met with when she started consulting with gynaecologists about it. Erin was confident that any surgeon would surely assess her history with PCOS and endometriosis and agree to do the procedure, but that’s not what she found at all.

Instead, gynaecologists turned her away, telling her that she was simply too young for them to go ahead with the operation.

“They were always like, ‘Sorry, I can’t help you with that’ and they would palm me off to the next guy,” she says.

One gynaecologist even told Erin that he refused to do the procedure because he had too many patients that had tried to sue him after going through with hysterectomies. Erin thought it was unfair for him to place that burden on her and even offered to sign contracts that would waive her ability to sue after they had completed the procedure. She was still turned away.

Doctors would frequently ask her about her future as a mother, interrogating her decision and assuring her that she would change her mind. They asked if she had a boyfriend and what he would think of her undergoing a hysterectomy.

“I was like, I don’t give a shit how he feels,” she says.

“One doctor said to me ‘You might go to a baby shower one day and get super clucky and you’ll be thanking me that I didn’t take your uterus out and I’m like, ‘Who the f--k says that? No, I don’t get clucky at all.’... When people say ‘Oh my ovaries are hurting’ when they see a cute baby, I’m like, ‘My ovaries are hurting 24/7 this baby is making it worse.’”

While Erin does not want children, the question of having a hysterectomy can be more complicated for women who are living with extreme pain caused by endometriosis and who feel strongly that they want to fall pregnant and give birth.

Do women have the right to decide when to have a hysterectomy?

The choice to have a hysterectomy to treat endometriosis pain, while frequently effective, can be a shattering decision for women who understand that they are giving up the possibility of having more children, or any children at all.

It’s not a choice that is taken lightly and for some women, they choose to bear the pain of living with endometriosis rather than miss out on the opportunity to be pregnant.

Alana, a 31-year-old software manager, has lived with severe endometriosis symptoms since she was a teenager and tells Mamamia that she has two young children and is waiting until she is completely confident she doesn’t want more before she has a hysterectomy.

“I wasn’t sure if I wanted kids,” she says. “It was until I was faced with the very real possibility that I might not be able to have them, that I realised how badly I did actually want a child.”

However, for other young women, they find that their quality of life is simply too severely impacted by life with endometriosis, even if parenthood is important to them.

Writer and creator of the groundbreaking series Girls, Lena Dunham, wrote in Vogue in 2018 about her decision to have a hysterectomy at 31-years-old, despite not having yet had children and feeling profoundly that she wanted to become a mother.

Dunham writes that she “never had a single doubt about having children. Not one, since the day I could understand how families were made… But I know something else too, and I know it as intensely as I know I want a baby: that something is wrong with my uterus.”

Dunham’s essay reflects on the enormous loss of undergoing a hysterectomy so early in life but also asserts that it was the right decision for her. She explains that the pain of living with endometriosis was simply too debilitating and rendered her “choiceless”.

But are young women given this choice freely?

Associate Professor Healy is a women’s health expert and endometriosis specialist says that, as in Erin’s case, there can be tension between patients and surgeons when it comes to assessing whether a hysterectomy is the right choice. He says that within his own practice, he tries to avoid paternalism when he’s consulting with younger patients about hysterectomies, but he also acknowledges that there is a “dogma” in training around it.

Traditionally, doctors have been taught to resist performing hysterectomies on people under the age of 35-years-old (in fact, the same guidelines exist around vasectomies). Associate Professor Healy says that these aren’t hard and fast rules and there is no particular scientific logic to it, it’s just a standard that has been built into practice.

But for people like Erin, this standard can feel like an unfair obstacle and bring them into direct conflict with the people that they are seeking help from.

“The difficulty with that is that you’re imposing some paternalism on a patient in their decision-making because you’re saying ‘You’re under 35, you haven’t had children, you can’t know your own mind.’ That’s the implication behind it,” Associate Professor Healy says.

Associate Professor Healy says it can be really tricky for a lot of people choosing to have hysterectomies but he also points to research (currently heading to publication in Australia) that shows that age does not correlate with regret following hysterectomies.

“The thing that correlated with regret was a desire to have children… A lot of people do it as a tradeoff, they look at their quality of life [with endometriosis] and it’s not good and they have a hysterectomy to try and improve their quality of life and give up or sacrifice the option of having kids to get that improvement in quality of life – those people often have regret.

But often there will be regret but they’ll still be relieved that they had the surgery because they’ve got their quality of life back.”

Can a hysterectomy treat endometriosis pain?

A hysterectomy is an operation to remove the uterus. There are different variations of hysterectomies, depending on whether or not accompanying organs around the uterus, like the cervix, fallopian tubes, and ovaries are also removed during the operation.

In Australia, hysterectomies typically remove both the uterus and cervix, which is otherwise known as a ‘total’ hysterectomy.

While endometriosis does not have a cure, a hysterectomy can provide treatment for severe pain. It’s difficult to pin down exactly how common having a hysterectomy for endometriosis treatment is in Australia, as there aren’t definitive statistics. Around 30,000 women have a hysterectomy in Australia every year but it’s unclear how many of these procedures are undertaken to manage endometriosis pain.

Associate Professor Healy explains to Mamamia that hysterectomies are quite effective for endometriosis treatment – but there are also aspects to the outcomes of the procedure that can be unpredictable. A lot of this comes down to questions around how endometriosis actually forms in the body.

“The main theory that people believe about how endometriosis occurs is that when you have a period, blood with some endometrial cells goes backwards through the tubes, sloshes around in the abdominal cavity and sticks and grows,” Associate Professor Healy says.

However, it’s not uncommon for women to experience endometriosis growth after a hysterectomy, in fact, Associate Professor Healy encountered this recently in his own practice.

A patient who had her hysterectomy about six years ago returned saying that she was experiencing increasing pain. At first, Associate Professor Healy says he was reticent to operate again and offered other treatments but the patient was adamant that she wanted another laparoscopy.

“I did another laparoscopy and she had three areas of endometriosis. So the possibilities? The first possibility is that it was there at the time of the hysterectomy and I just didn’t see it – and no matter how good we are, we all miss things, so that’s always a possibility.

The second possibility is that maybe sometimes endometriosis grows by a different mechanism. There are about half a dozen different hypotheses or theories of how endometriosis can grow – and all of them are sometimes right,” he says.

Associate Professor Healy estimates that the chance of developing more endometriosis following a hysterectomy (assuming that the surgeon has cleared all of the disease when performing the operation) is around 10 per cent.

For Erin, who underwent a hysterectomy earlier this year, she has described the relief of having this procedure as “winning the lotto”.

Erin, who is now 28-years-old, says she dreamt a little about having children when she was younger – she had always wanted twin girls. But the more surgeries that she underwent, the more complications and pain she endured, the more, she says, she “put a wall up” and accepted that becoming a biological mother was not going to be part of her reality.

“I think it’s because I’m associating [having children] with pain – and when you’ve gone through what I’ve gone through, the last thing you want is to have a child.

“A lot of women that I’ve spoken to that have had hysterectomies told me that, you know, just be careful about the first week out post-op, you might get really depressed and down and you’ll cry and you’ll mourn and you’ll grieve about your uterus and the loss of having children. And I haven’t cried.”

In fact, the portrait that Erin paints of her life post-hysterectomy is one of marked joy. Following the surgery, Erin was also diagnosed with adenomyosis (a related condition that often accompanies endometriosis); she says that the confirmation of this condition only made her wish that she had undergone the hysterectomy earlier.

Erin works as an ambassador for Endometriosis Australia and she continues to document her life on Instagram and educates her near-half a million followers about the conditions she has lived with.

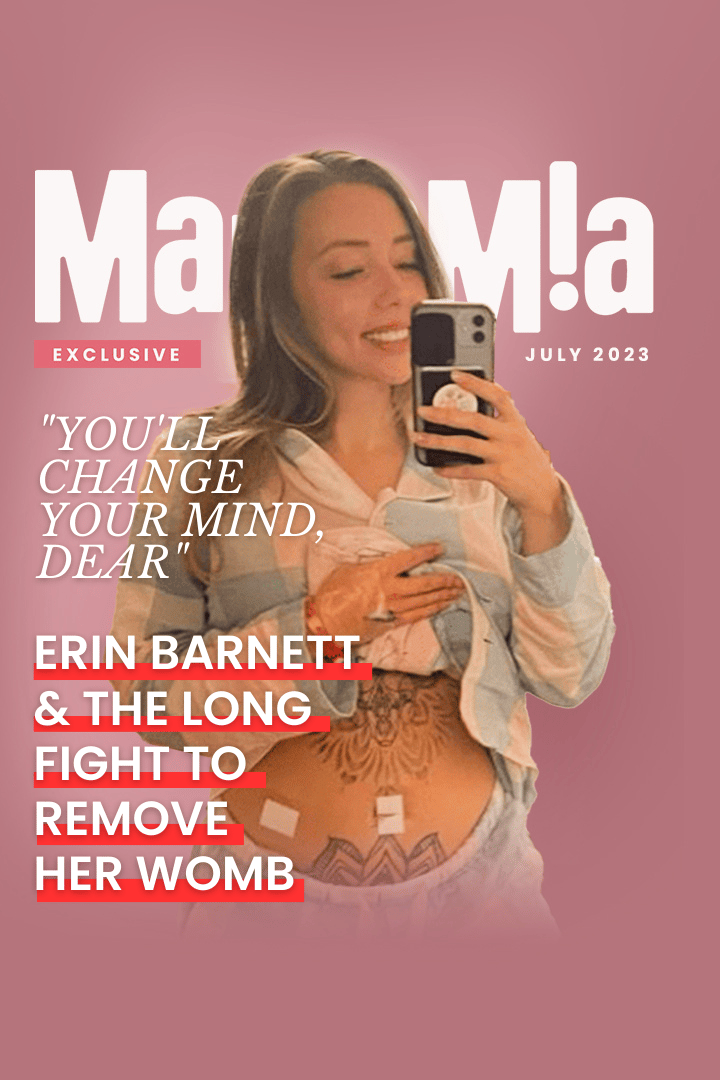

She posted to her Instagram the day that she had her hysterectomy. In the photo, she has her pyjama top lifted and she’s beaming at the mirror, her tattooed stomach exposed, with surgical patches on it.

She writes that the surgery went well, that she was glad that she “never gave up advocating” for herself and asks her followers to remember: “we are all amazing with or without kids.”