It was a warm January morning in 2017. Emily Hall was 37 weeks pregnant. It was early and her husband Matt, a pilot, wanted to go dirt bike riding with a friend. He woke Emily to say goodbye. He told her he loved her and whispered to her pregnant belly that he was "ready for him to come out now." He said he'd be home around 3.30pm and left.

That would be the last time Emily saw him alive.

As the afternoon passed, she tried to call and text him. She’d even reached out to her friend, whose husband was riding with Matt.

“But I didn't hear back from anyone,” Emily tells us on No Filter. “I heard a knock at the door — and it was two police officers.”

The father-to-be had collapsed while riding in Beerburrum State Forest, Queenland. His temperature was 42 degrees when paramedics arrived on the scene. Matt’s organs began shutting down when the rescue helicopter landed, and he tragically died shortly after.

He was just 29 years old.

At that moment, 30-year-old Emily’s reality changed forever.

Fluctuating between shock and the depths of pain, the weight of what was to come hit her with brute force.

“When people say your heart is broken, it literally feels like your heart hurts,” she says. “You just think that they're gonna turn up at the door.”

“I just thought I was in some sort of nightmare.”

For Emily, the next two weeks felt like a heavy mist of darkness.

“I don't know how I got through them,” she shares.

Everywhere she looked, there were footprints of Matt. His phone on his bedside table. His mug in the kitchen.

“Even the clothes he took off the night before were sitting in our bathroom for a good six months — just on the floor, sitting there.”

Then, on February 6, 2017 — just weeks after Matt passed away — Emily gave birth to their baby boy.

She called him the name they’d both picked out: Harry. Harrison Matthew Hall.

It was bittersweet. Like “having a piece of Matt forever” but feeling “grief and joy at the same time.” She says, “I desperately wanted this baby. I needed this baby.”

Suddenly, Emily found herself attempting to navigate the pain and grief of losing her husband while learning how to become a new mum.

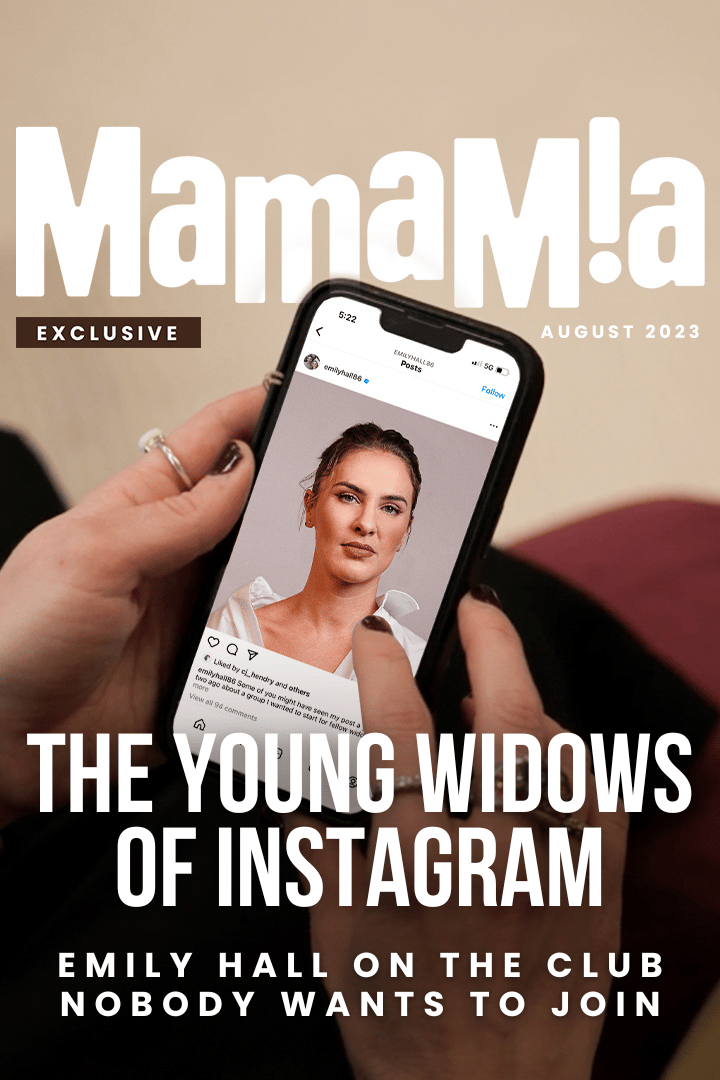

“I was desperately looking for someone who understood what I was going through,” she says. “I started grieving on my Instagram, writing how I was feeling. It was almost like a diary entry for myself — I was giving myself a pep talk. I wasn't ready to give up.”

The need to find people who understood her grief was so great she decided to create a support system herself. Not only did she want to build a place to help other people cope with grief, but she also wanted to challenge the idea of what a widow looks like. Put simply, being a widow doesn't have to be the end of the chapter.

“I found widows groups on Facebook — but they were all older American women who were all just whining about day-to-day stuff. And I had decided quite early on that I wasn’t going to feel sorry for myself.”

“Because yes, these really terrible things happened to me. But I'm not going to let it define me — I had just turned 30 years old. I decided that I wasn't going to let this be the end of my story.”

So, she created a group.

It’s called the ‘Young Widows Club’.

The Young Widows Club is a space that provides support in a world where there’s no guide on what to do when your partner dies.

It’s made up of a strong community of women who connect with each other online in the darkest of moments, helping each other cope with their grief following the early death of their significant other. They vent their frustrations and anger. They ask questions and give advice. They try to meet up quarterly in Brisbane – but Emily would love to branch out to other locations. They laugh and cry — all while being heard and understood.

“Now, there are almost 150 girls,” Emily tells us.

You don’t have to be female or married to join — but members of the group are all young to be widowed.

***

As a society we have a very clear picture of what grief is supposed to look like when someone loses a partner or loved one. When really, psychotherapist and author of It's OK that You're Not OK Megan Devine tells Mamamia, there’s no perfect depiction of what grief actually is.

Making the grieving process more complex is our culture’s preconceived notions that while death and loss may be quick and intense, grief isn’t lasting. But you can’t put a time limit on grief and mourning.

And there’s not always such a thing as ‘closure’.

Part of the issue with how we think about grief is seeing it as an emotional event. But it’s not. Grief, Devine says, is a full-body, full-mind experience.

“Your body is essentially doing whatever it needs to do to cope — and exercising the fear that someone you love is not coming back.”

“You’re not just missing the one you’ve lost; your entire physiological system is reacting, too — heart rate, respiration rate, cognition, memory, digestion — so just biomechanically, grief changes you.”

Devine is someone who knows grief from the inside out — personally and professionally.

“I started my professional career as a psychotherapist in 1999. For nearly a decade, I worked with people on issues related to abuse, trauma, addiction, and grief.

“And then, on a beautiful, ordinary summer day in 2009, I watched my partner drown,” she says.

“Matt was strong, fit, and healthy. He was just three months away from his 40th birthday. With his abilities and experience, there was no reason he should have drowned. It was random, unexpected, and it tore my world apart.”

“In those early days of my own grief, real talk — real help — was extremely hard to find. Back then, there were very few people talking about grief as anything other than a disorder, or some unfortunate thing you just had to shake off and get back to your normal, happy life. Put the past behind you! Focus on gratitude! It’s so unhelpful.”

“My endless search for real support and understanding, with all its frustrations and wrong turns and disappointments, is why I do the work I do now.”

Grief also impacts your sense of the world as a safe and predictable place, says Devine.

“This is especially true if your loss was sudden or unexpected. Your world has changed, but everyone else goes along like nothing’s happened.”

And for young people, this can make grieving feel painfully lonely.

As Emily recalls, “People used to say, ‘You’re young. You’ll find love again’. But it was like, stop saying that to me. Stop giving me a silver lining.”

***

Holly, 35, was one of the first who joined the group in 2021, shortly after her husband Paul passed away suddenly from a cardiac arrest. She was six months pregnant at the time.

She tells us the group has given her reassurance that she wasn't alone in her grief, and helped her feel a part of a community. “I was sick of seeing everyone's 'perfect happy lives' on social media, even my own friends,” she says.

“Whenever I have bad days, I think of all my widow sisters and remind myself that I'm not alone on this journey and think how strong we all are and how proud our partners would be of us. They all inspire me in many ways and I honestly don't know where I'd be without them.”

There’s also Dayle. She was 28 when her husband Benjamin was diagnosed with acute myeloid leukaemia. She says that even when she was contemplating losing Ben, she had no idea what it would be like.

“You lose your past, your present and your future in one hit. All the shared memories you had: gone. Your every day: exactly the same, but without your person to share the highs and lows with. Your future: uncertain. All the goals you had together as a couple — no longer relevant.”

While most of the initial connection and conversation happens on social media, the group arranges regular catch-ups with whoever is in the same area and able to join.

Dayle says, “After our first meet-up, I’ve stayed in close contact with two widows and we message frequently and catch up once a month or so.”

“I have amazing and very supportive friends and family who have been with me every step of the way. But there is something to be said about being able to share your feelings with someone else who has gone through a similarly traumatic experience.”

“You don’t need to explain why you feel a certain way, or justify the thoughts you have — they just get it. And that’s what’s been so great about the Young Widows Club.”

Tara is another member of the club. She became a cancer widow during COVID-19.

“I have two neuro-diverse children and our family is overseas, so my experience of widowhood has been bumpy, especially as grief services were not considered ‘essential services’ for so long,” she tells us.

“A community like this is so important for our sense of belonging. I love that we can unpack issues here that others don’t get, surrounded by kindness.”

“Young widows are right in the middle of the busiest nesting phase of our lives and so the impact of losing our partner extends logistically, domestically, financially, and intimately. This means that every day, ‘triggers’ come up, and healing takes years — not just whatever annual leave you have left.”

One of the most integral things about this support group is that members essentially help one another understand that growth and new beginnings are possible after loss.

Whether it’s moving to a different city, starting a new career, having new experiences, making new friends, or — dating.

As Devine says, entering a new relationship after death is one of the most common or shared experiences no one openly talks about. “There’s a lot of judgement around dating, hook-ups, or new relationships after someone has passed.”

For Emily, building that family unit with her son and a partner was something she longed for — but she found that navigating dating and mourning at the same time was complex and unpredictable.

“I didn't feel disloyal on the dating apps because I knew what kind of man Matt was, and I knew he would have wanted me to be happy.”

“I didn’t want to be ‘the widow’,” she says. “I used to smile in photos and just fake it. I’d wonder to myself, am I ever going to smile and actually mean it, actually be happy.”

“My father-in-law told me that he wanted me to find someone else and not be on my own forever, which really meant a lot to me.”

Emily met her now-partner Dave after a year and a half. She says, in hindsight, it was “too early”.

“I was very lonely and desperate to feel like everyone else and feel part of a family. I wanted to start again, but it was hard. I just wasn't ready. Dave and I went through a lot in the early days,” she admits.

When you lose someone, you put them on a pedestal as someone who can do no wrong, Emily says. And that makes a new relationship with a new person complex on so many levels.

“But your heart grows. I can still love Matt and I love Dave with everything that I've got. It’s about holding the joy and the sadness in the same place and navigating the invisible boundaries.”

In 2020, three years after Matt’s death, Emily and her partner Dave welcomed a baby boy — Oliver Mosman Downey.

For Emily, she says expanding her family was about being able to hold the joy and the sadness in the same place.

“It's important to me to keep Matt alive. Harry has photos of Matt up on his wall and he knows Matthew is his dad in heaven — I'm not going to pretend it didn't happen because, of course, it happened.

“But it doesn't feel like Oliver is Dave’s biological son and Harry is just his step-son. They are both his boys.”

When the Young Widows Club first started out, Emily says there were around 10 members — and a lot of them had children.

Like her, they struggled to navigate the grieving process not only for themselves, but with young kids who had lost a parent. “It felt heavy,” she shares.

“One of the girls, who I'm really close with now, she literally came [to a catch-up] with her three-month-old baby. Her husband had just passed away about eight weeks earlier.”

“Just thinking about those early days, and how I never want to be back there ever in my life — it was really difficult. It is really heartbreaking to see them like that. But we’re all here for each other, and I truly mean it. Because I wish I had that.”

Without groups like the Young Widows Club, it becomes almost impossible to think how young women, many of whom have children, essentially enter a world of darkness and mourning, without a roadmap.

And as a society, the outdated notions we have of grief, and the tools we attempt to use to help these people, are broken. Unhelpful. And often do more harm than good.

As Devine says, emotional topics will always feel daunting when we don’t feel like we have the skills or experience to deal with them.

“The examples we have of what grief is and how we talk about it are horribly out of date and unhelpful,” she says. “There hasn’t been a change in the ways we talk about grief in over 50 years.”

“We’ve been taught by books, media, and the medical profession that grief is a problem: it’s natural to have some feelings after someone you love dies, but you should be back to ‘normal’ very quickly.”

This creates an unattainable goal in which grieving people think they’re supposed to achieve, says Devine. And it’s not healthy.

“We don’t know how to have real conversations about grief in any form. And no one wins.”

So what is our role when dealing with someone else’s pain? How should you behave if someone close to you loses their partner?

“It’s not your job to fix someone’s pain for them,” Devine says. “Most people want to be heard and acknowledged, not talked out of their feelings. That’s true in any situation, from a rough day at work to the death of a partner: don’t rush in with advice, don’t talk them out of their pain.”

As Emily puts it, “Your trauma is not other people's entertainment, it's your story.”

“And there’s more to me than grief.”