Content warning: This story includes descriptions of child sexual abuse that may be distressing to some readers.

How does a child survive years of unimaginable abuse?

She splits. And splits again. And again. And again. She does survive. But not without consequences.

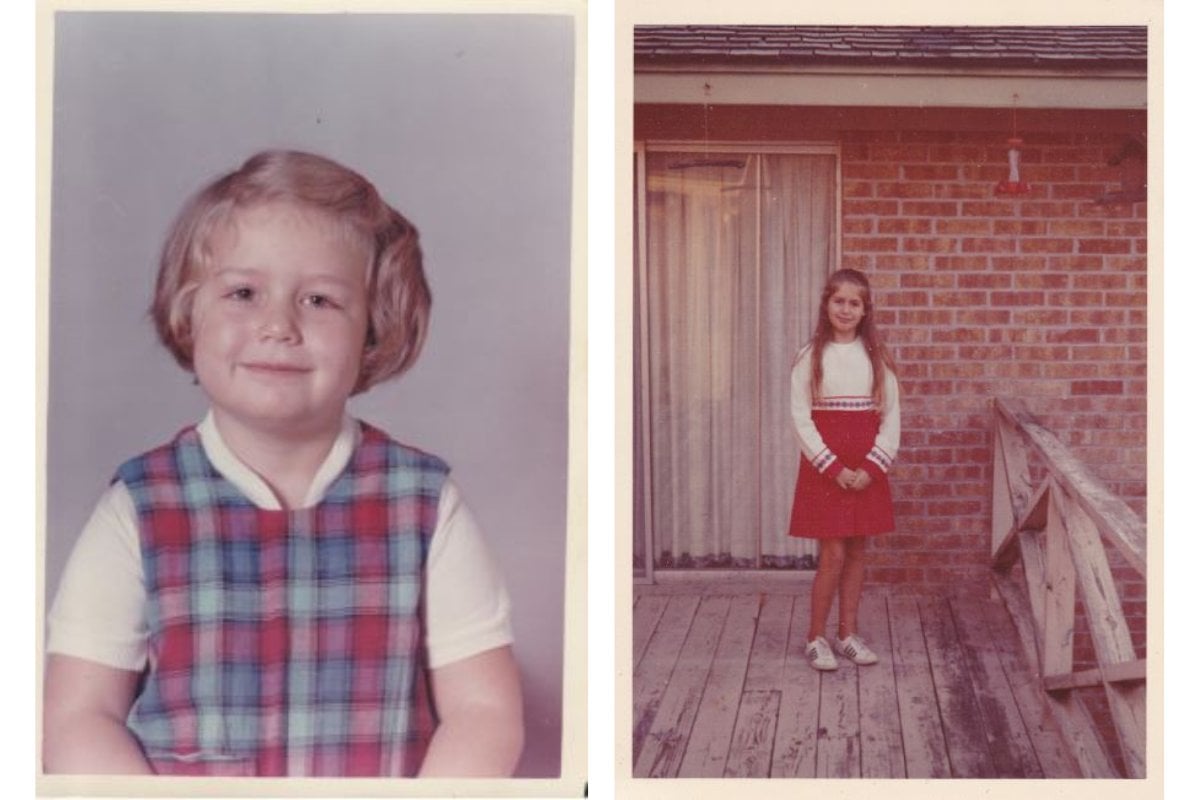

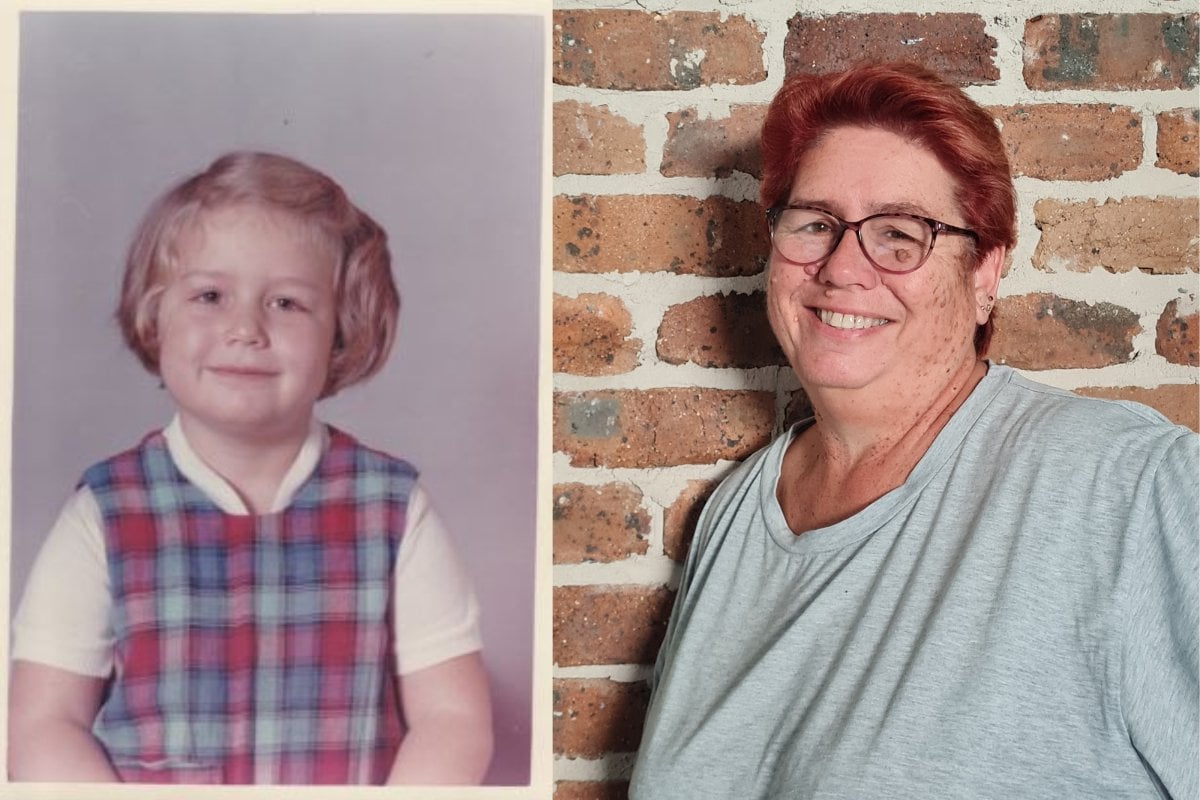

From the age of three, author Maggie Walters faced abuse that is unimaginable to most. It was physically, psychologically and emotionally sadistic and didn't end until she reached 16.

When the abuse began, Maggie went to the deepest, darkest part of her mind to protect herself. She created multiple personalities to cope.

"The belief had been seared into me that no-one could really be trusted. My soul had been so decimated. It seems as a child I had an innate ability to sense new danger," she tells Mamamia.

Maggie was born in England. She and her family — her mother, father and two older brothers — immigrated to the US when she was three years old.

Watch: Maggie shares her story with Mamamia. Post continues below.