Content warning: This story includes descriptions of sexual abuse.

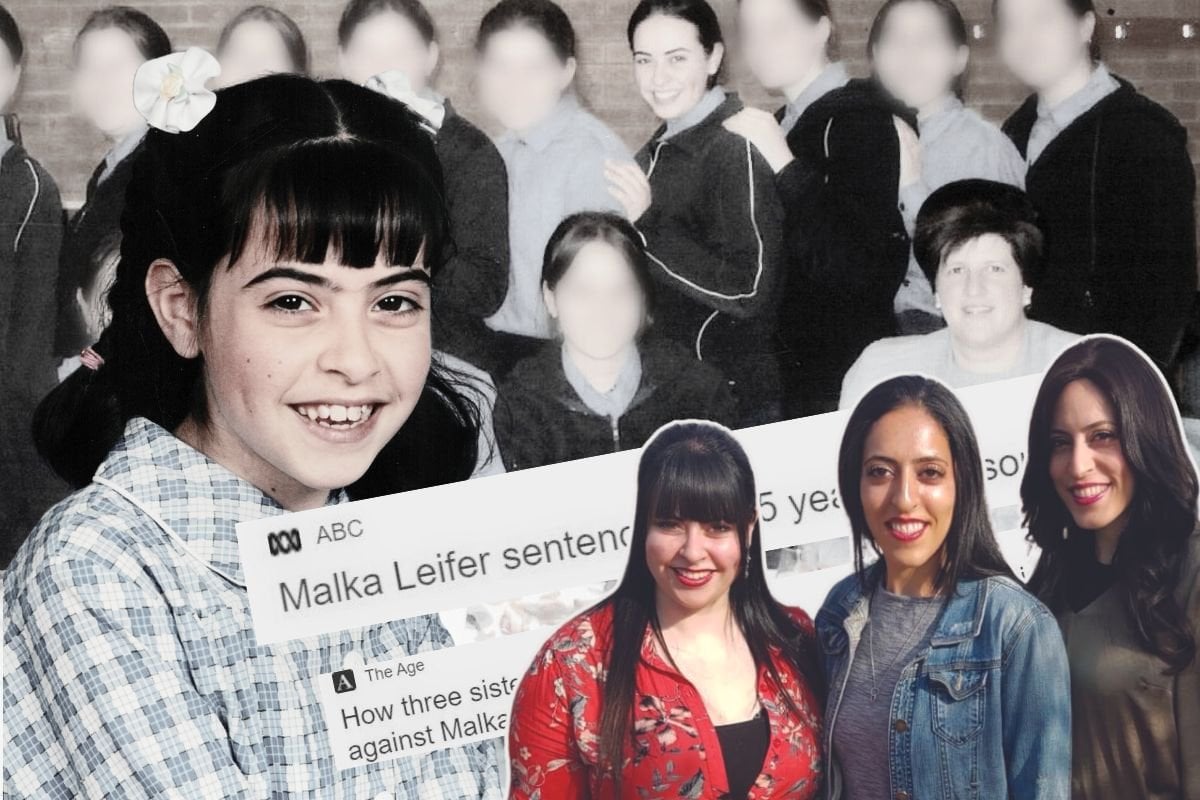

In August 2023, Dassi Erlich breathed a huge sigh of relief as she watched her former high school principal be sentenced to 15 years in prison.

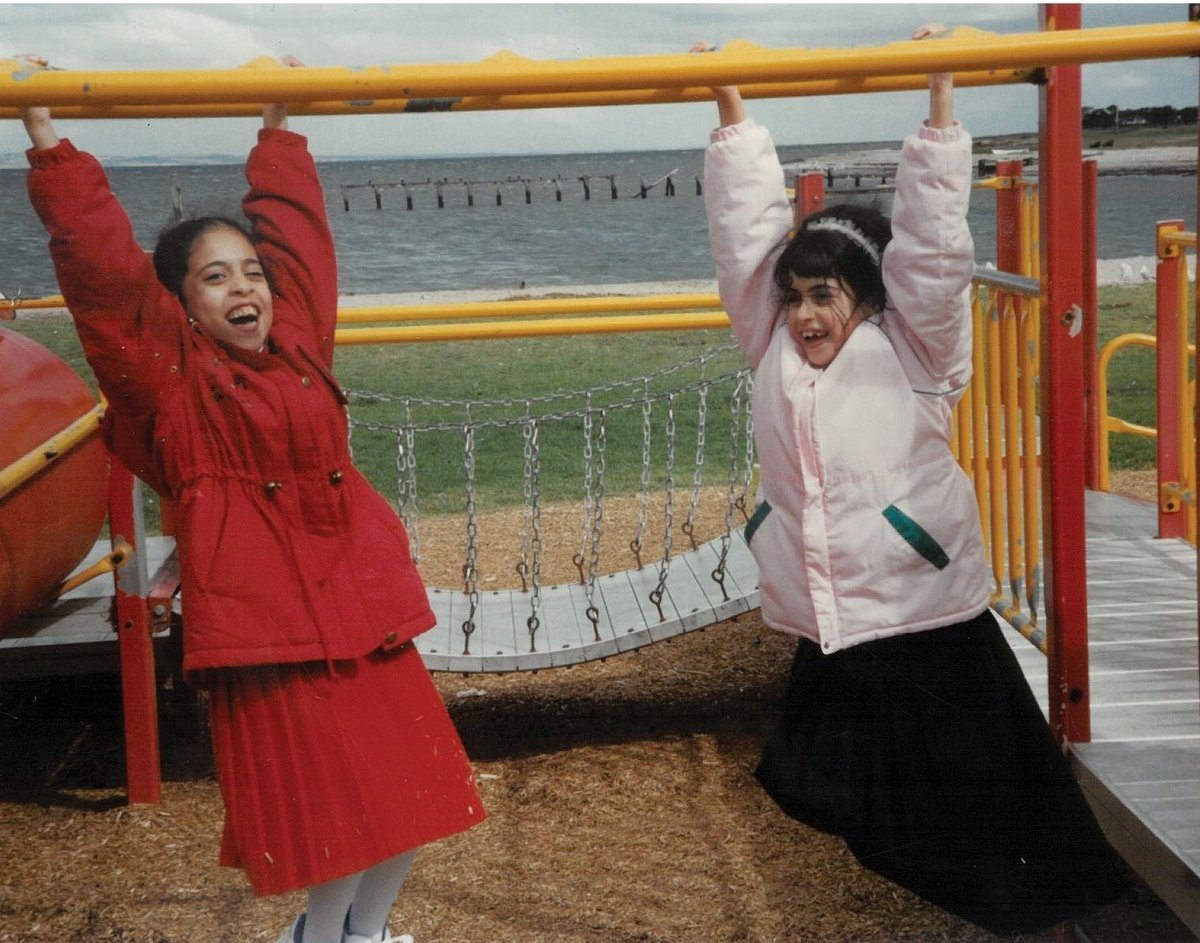

She fought for 15 years to hear those words, after suffering ongoing sexual abuse at the hands of Malka Leifer as a teenager.

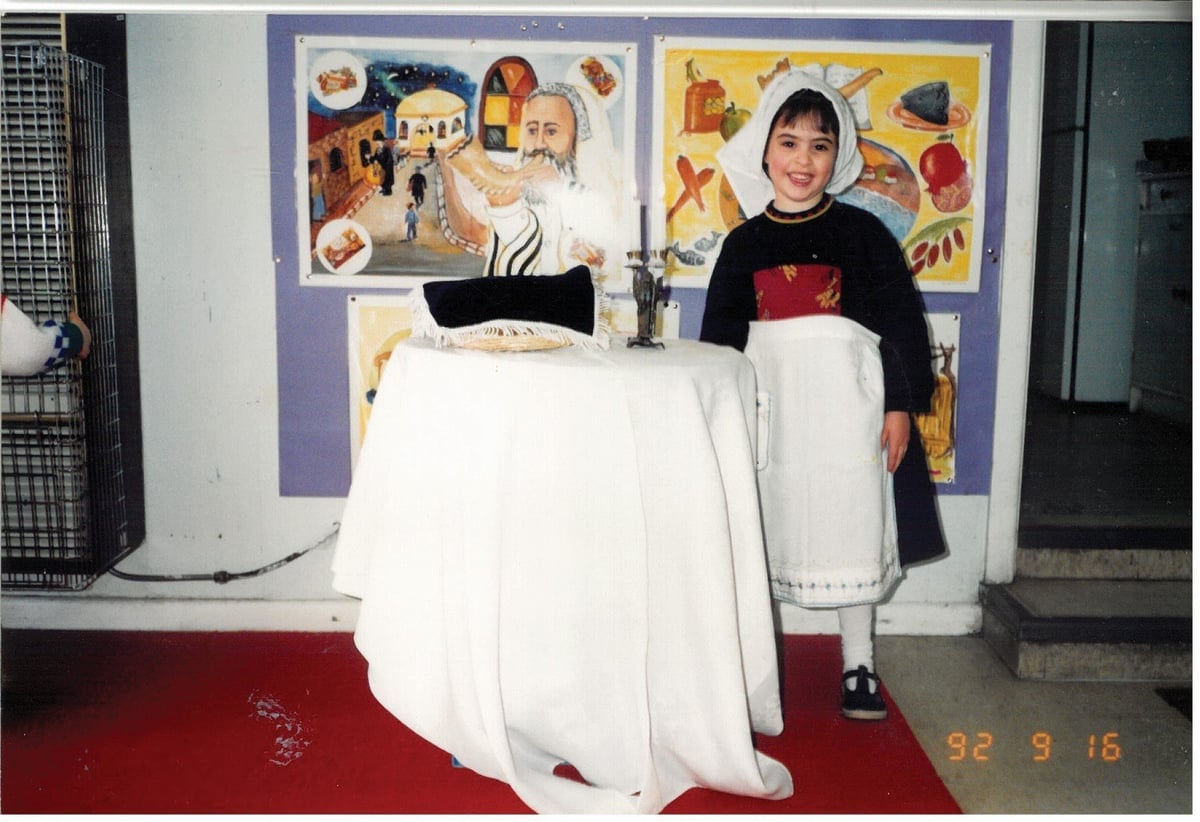

Leifer had been in charge of the Adass Israel School she attended in a close-knit and very isolated ultra-Orthodox Jewish community in Melbourne's south east.

The former teacher was convicted of 18 charges of sexual abuse including rape and indecent assault against Dassi and her sister Elly. She was acquitted of nine charges, including five relating to their older sister Nicole.

Their story received worldwide attention. They were the sisters fighting to get Leifer extradited back from Israel after she fled there soon after the allegations came to light. It took 70 extradition hearings and 13 years to bring her back to Australia.

"When I gave my testimony and during those awful five days of cross-examination, I couldn't see her. I didn't want to see her. There was no desire in me to face her," Dassi tells Mamamia's No Filter this week.

"I did when I gave my victim impact statement, I looked up and saw her. She had this utter look of disregard. There was no remorse whatsoever."

Listen to Dassi Erlich tell her story on Mamamia's No Filter podcast. Post continues after audio.

Top Comments