Cooper was playing an innocent game of tag in the schoolyard when it happened.

The nine-year-old fell over and hit his knee on a step. Not feeling badly hurt, Cooper dusted himself off and rejoined the game with his pals.

When he went home that afternoon, he told his parents that he had "a bit of a sore knee". They inspected it, but couldn't see anything wrong.

Things went on as usual. Until four days later, Cooper woke up in screaming pain.

Watch Dr Joshua Pate on why pain feels different for everyone. Post continues after video.

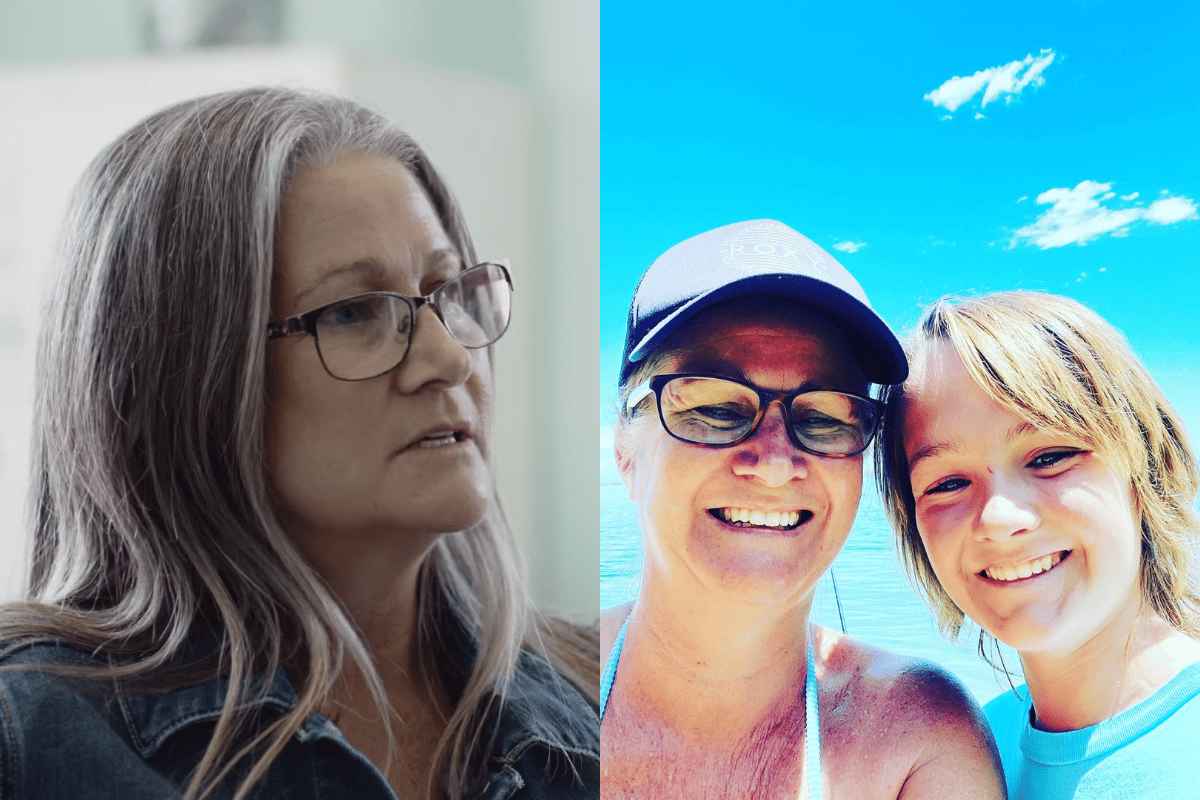

"We couldn't touch him. He wasn't able to walk at all," his mother Melinda Smylie told Mamamia.

"It was quite scary, not only for a nine-year-old, but for us as parents as well."

Eventually, Cooper was diagnosed with a rare condition called Complex Regional Pain Syndrome — chronic arm or leg pain developing after injury, surgery, stroke or heart attack.

"It is very hard to diagnose, there's no known cure for it, and treatment is difficult," Melinda said.