Danny is frightened of his dad. Every night he goes to bed and pretends to be asleep. He listens to his dad mistreating his mum. Danny thinks his life is normal until he goes on a sleepover at his best friend Alex’s house. Alex’s dad is kind and fun to be with, and Danny feels happy. Danny wishes his dad could be more like Alex’s dad. But what can he do?

Children are the smallest, often most silent, victims of domestic violence.

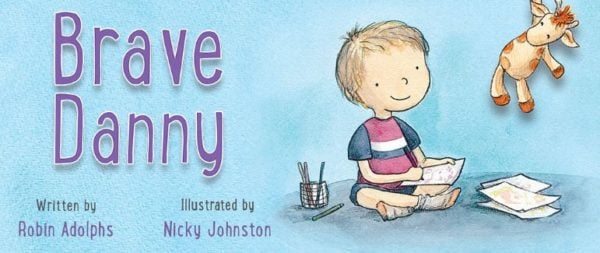

Now, there is a children’s book to help young people trapped in situations of domestic and family violence. Brave Danny is written to empower kids aged between four and eight to talk about their feelings, to teach them what a happy, safe family can look like.

Rosie Batty talks about her experience with domestic violence. Post continues below.

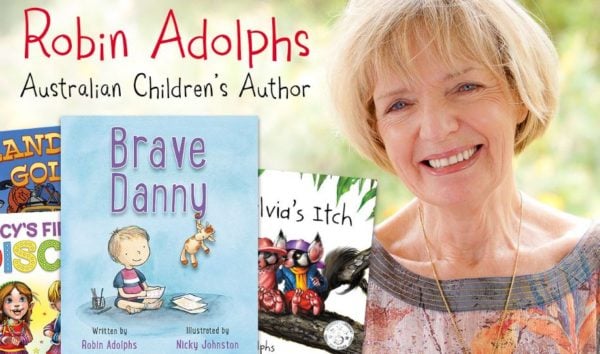

“The smallest voices are sometimes the most powerful,” author of Brave Danny Robin Adolphs, who also has a background in education, told Mamamia. “It’s important we help young people understand what domestic violence looks like – we need to break the cycle. Children are capable of learning and understanding a lot. What better way to learn about domestic violence than in a loving, caring way?”

The book, written by Adolphs and illustrated by Nicky Johnston, is an initiative of the National Rural Women’s Coalition (NRWC) and came after reports of increasing domestic violence in remote Australian communities.

“Domestic violence is an issue rearing its head in bush communities, particularly when natural disasters such as fires and floods occur,” NRWC Treasurer Alwyn Friedersdorff said. “When those things happen, domestic violence tends to creep in. We wanted to send a message to the youngest age group possible, to help build resilience to domestic violence at the earliest age.”

Top Comments

Thank you for writing this. Is an important book and is helpful for many children who live in this situation.