Bella's symptoms appeared suddenly.

"At the end of January in 2020, I was driving back from Wagga and something just came over me. I thought I was dying.

I thought I was experiencing a panic attack, but I had never had one before — and I was driving on the motorway, it was very scary."

Bella said she immediately pulled off the road before driving into Bowral to see a doctor, who agreed she was simply having a panic attack. She drove home to Sydney but continued to have these panicked episodes for the next two weeks. Each time it happened, she experienced the same overwhelming feelings of dread and terror.

Along with these psychological symptoms, Bella developed an onslaught of bizarre, seemingly unconnected, and disturbing physical symptoms.

"I started getting extreme fatigue, throat clearing, coughing, difficulty swallowing, feeling like I was choking,” she told Mamamia. “I started getting really bad chest discomfort, shortness of breath — those were definitely my worst symptoms. I just felt like I couldn't breathe."

Bella said she fell into a deep depression.

In the months prior to her first panic attack, Bella remembers her body had begun to change. She'd gained a little bit of weight that she describes less as putting on fat and more as "puffiness" but it didn't ring any major alarm bells.

"I feel like it was just inflammation that was maybe a gradual thing, I didn't notice it," she said.

When the more severe symptoms came on, they hit her like a wall.

The 29-year-old describes herself as a naturally anxious person and she had been prescribed antidepressants when she was around 16-years-old that she took for about a year. But this time, at 26-years-old, Bella could recognise that the mental health concerns she had experienced as a teenager were largely circumstantial — due to things going on in her life at the time. This felt markedly different.

She was freshly involved in a happy and healthy relationship, nothing in her life was challenging her, and she felt profoundly like she should have been content, if it wasn't for this overwhelming, implacable feeling that something was terribly wrong within her body.

Bella explains she was studying nutrition at the time and says it was this immersion in medical conversations and 'pure gut instinct' that led her to conduct her own investigation into what was going on.

Researching her broad-ranging medical and psychological symptoms and reading about other women's experiences online, she rapidly came to the same conclusion reached by thousands of women before her: her breast implants were making her sick.

At the time, Bella had been living with breast implants for nearly a decade, after getting a breast augmentation surgery at 18 years old. She said that she can’t remember ever feeling particularly insecure about her body at the time, she just went through with it because it was what her sisters had done before her.

There has been anecdotal evidence growing for years that some women who have breast augmentation surgery are developing symptoms like Bella did. And medical professionals are finally starting to take it seriously.

Approximately 20,000 women undergo breast augmentation surgery in Australia every year; around 75 per cent of these surgeries are for cosmetic augmentation and the remaining 25 per cent are for reconstruction. Since its introduction in the 1960s, breast augmentation surgery has become the most common surgical procedure performed by plastic surgeons worldwide.

There are multiple risks associated with both breast augmentation surgery and living with breast implants and these problems tend to crop up every few years in lawsuits and news headlines.

Breast pain, scar tissue, changes in nipple sensation, and dissatisfaction with results are some of the low-level issues that women may accept as a possibility when they get implants.

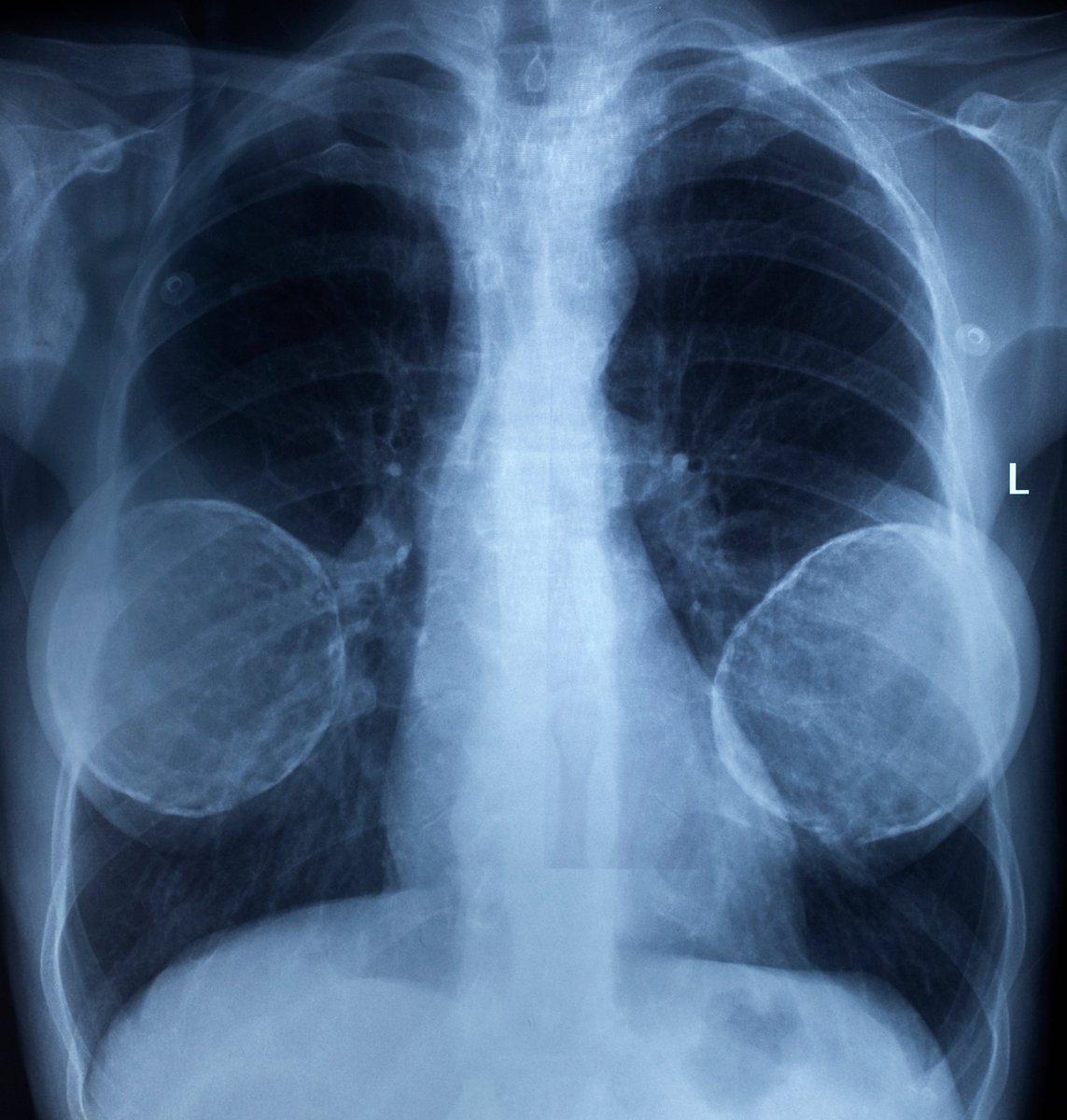

On the more severe end of the spectrum, there is the possibility of implants rupturing, wound infections, and breast implant associated-anaplastic large cell lymphoma, a rare type of non-Hodgkin's lymphoma — or cancer of the immune system.

It's difficult to establish how many people who have breast implants experience these complications because public health bodies don't know the exact number of people who undergo breast augmentation surgery but one study cited by Health NSW found that among nearly 6,000 people who had a second surgery for implant complications in 2018, one in five were found to have an implant rupture and four in every 1000 were found to have breast implant-associated anaplastic large cell lymphoma.

Then, there are the associations between breast implants and autoimmune conditions like rheumatoid arthritis, which have been discussed in medical literature since the 90s.

As for whether or not breast implants can cause the onset of autoimmune conditions, it's difficult to establish a causational link, and the research has been patchy and contradictory at times. As pointed out by Canadian researchers in one report the link between autoimmune diseases and breast implants is tricky to establish because ideally "to state causality, one must be able to demonstrate that the exposure to breast implants preceded the onset” of these diseases.

In other words, studies of autoimmune conditions would have to be able to follow women before they ever made the choice to undergo breast augmentation, which is logistically problematic, to say the least.

But besides these documented risks, there are experiences like Bella’s that are even less understood.

What is this new condition?

Chronic fatigue, joint pain, brain fog, dry eyes, headaches, anxiety, depression, breathing problems, rashes and other skin problems, hair loss, sleep disturbances, and gastrointestinal problems are amongst a broad constellation of symptoms that seem to develop in some women with breast implants.

This seemingly random collection of symptoms is commonly referred to as Breast Implant Illness (or BII) but Professor Anand Deva, who has been researching these symptoms among Australian women, prefers a more scientifically accurate term: Systemic Symptoms Associated with Breast Implants (or SSBI). Professor Deva advocates for the use of this term because BII implies that there is an official, medically diagnosable condition — and this is simply not the case.

But the current lack of broad medical understanding doesn't make it any less of a real experience for women who are living with these disconcerting and, at times, brutal and debilitating symptoms.

For Bella, stumbling across descriptions of SSBI on the internet was a lifeline for her during a dark and confusing period. She had spoken to multiple GPs who brushed off her claims and attributed her struggle to the onset of a mental health condition.

One Facebook group dedicated to assisting women who are experiencing breast implant illness has nearly 180,000 members from around the world. The group's description touts it as a resource that creates "an uplifting space to support you through breast implant illness, explant, detoxification and healing from saline and silicone breast implants because we've experienced it".

Women report to the group with photos of their progress and their choice to remove implants (otherwise known as explanting) once SSBI develops. One photo of a woman with frowning emojis obscuring her breasts tells the group, "This is me and in less than 12 hours these 9-year-old silicone implants will come out. To look at this picture is hard. It's been a really, really hard few months. Depression and anxiety are awful and the usually fit me is suffering."

Charlotte is a 27-year-old public servant who also developed an inexplicable collection of symptoms after getting breast implants when she was 19. She opted for a surgeon in her hometown who was recommended by friends and after only one consultation, Charlotte decided to go through with the $20,000 augmentation surgery.

Charlotte said her decision to undergo breast augmentation surgery at that age was "purely cosmetic" and one that she dived into quickly. "I just wanted to have larger breasts because, at the time, that's what I thought would deem me attractive,” she said.

She told Mamamia that seven months after getting her implants in 2015, she broke out in a strange rash that travelled up her chest and spread to her neck and across to her ears. She describes the next seven years of living with implants, until she had them removed in February of 2022, as a "long, invasive time".

Charlotte suffered from extreme fatigue, brain fog, and chest pains that disrupted her social life. She said that, like Bella, she felt remarkably validated by the accounts of other Australian women when she discovered these online communities and realised that she wasn’t alone in her experience.

"If it wasn't for that Facebook group, I think I would have struggled because I would go on there nearly daily and people would post all of the symptoms they were having," Charlotte said.

"[Living with SSBI] was isolating and really hard to share with close family and friends and even my husband at the time because no one had really heard of it. So it was really hard to convince people I was going through this and it was a pretty lonely time. The online forum and the support from the community of women — that helped immensely."

Once Bella scanned these communities and recognised the issues she was having could have been connected to her implants, she quickly went back to see the surgeon who originally performed her augmentation operation.

Bella said that the conversations she had with her surgeon were highly emotional but also somewhat reassuring considering the journey that she had taken to get to that point and the way that she had felt dismissed by so many doctors before him.

"To go in there and for him to tell me 'You're not crazy, this is a thing' I literally broke down into tears because everyone was telling me that I was crazy — not in so many words but they were saying 'No, you're just depressed' or 'No, you're just anxious'. And there were some days I couldn't get out of bed and so for him to turn around and tell me I wasn't crazy, it was just the best news ever."

Her doctor also reinforced to Bella exactly how many women appeared to be having an experience similar to hers: "He said 'I'm currently taking out more implants than I'm putting in'. Those were his words." In fact, according to Medicare data, over 4,800 women had breast implants removed in the year from July 2021 to June 2022.

Bella's SSBI came on suddenly in January of 2020 and four months later, she had her breast implants removed. She said that her symptoms disappeared almost immediately.

Charlotte, who had her implants removed in early 2022 and has been involved in Professor Deva's research, said that after her explant surgery, the 30 symptoms that were recorded before she had the surgery disappeared almost entirely and only a few lingering low-level symptoms remain.

Professor Deva told Mamamia that this dissipation of symptoms seems to be common among women who develop SSBI and then have their implants removed. His research team has tracked the remarkable progress of a cohort of Australian women who have undergone the second surgery to take implants out.

"What's interesting is that women have a significant reduction in the number of symptoms and a significant reduction in the severity of their symptoms — it's off the scale," he said.

As the research stands, there is no understanding, established through rigorous scientific trials, of what might be behind SSBI. But Professor Deva certainly has his suspicions. He recently presented his first findings from a large, ongoing study into SSBI at the Annual meeting of the American Society of Aesthetic Plastic Surgery.

"In our study of around 80 women now that have had their implants removed, there was a slightly higher rate of bacteria growing on the surface of these implants. And one of these blood tests called the C-reactive protein [test], which measures generalised inflammation, was moderately elevated in this group of women with systemic symptoms and breast implants... It's not definitive proof but if we found absolutely no difference, I would say maybe it's not inflammation."

There is also the consideration that any implant anywhere in the body for any reconstructive or cosmetic procedures could pose the same risk. For example, orthopedic implants have been associated with developing lymphoma as well as other systemic symptoms similar to what's being reported in women experiencing SSBI.

Professor Deva explains that with any implant, including transvaginal mesh and orthopedic implants, low-grade infection can be a problem because bacteria can attach onto prosthetic surfaces, which the immune system will continue to battle against.

"That uncorrected infection and your body trying to get rid of it will eventually exhaust the immune system — and then you get autoimmune disease. So there's a biological pathway there," he said. Professor Deva refers to these connections as "little clues" from other implants and the way they can cause similar symptoms but he also concedes that there is a long way to go with the research to say that this could be the definitive cause of SSBI.

Professor Deva also believes that there may also be, strangely, an emotional aspect behind SSBI and a 'mind-body' connection with inflammation that may amplify symptoms when women find they're being dismissed by doctors.

He believes that when women are pressured into getting breast implants and aren’t informed of all the risks, that stress and disempowerment may intensify the experience of SSBI. Deva believes that the risk of developing severe symptoms could be mitigated by ensuring that all women undergoing breast augmentation are adequately educated about the risks and they approach it as an informed decision.

Unfortunately, this highly cautious, highly informed approach doesn't seem to be a norm across the breast implant industry. There are multiple cosmetic surgeons around the country, who instead attract consumers through attention-grabbing, glitzy, and highly sexualised imagery on social media that Professor Deva believes may be contributing to overall issues of disempowering women and placing them under undue pressure.

"You might have a well-trained doctor but you know, that's a commercially driven practice. If they're putting out these beautiful images of 'before and afters' and women in lingerie and what have you, that's not really being honest with women," he said.

Charlotte said she agrees with Professor Deva's assessment that she should have been educated more thoroughly about the risks. She believes she rushed into the surgery because she thought it would make her feel more attractive at a time when she was feeling insecure and it’s a decision she regrets. “I've had a bit of a mental health journey since then," she said.

Fittingly, however, Professor Deva's research coincides with a large-scale overhaul and reassessment of Australia's cosmetic surgery industry. In September of last year, health ministers from across the country agreed to a suite of industry reforms, including developing a national education campaign that promotes consumers making informed decisions around cosmetic procedures, which launched in early April this year.

Broad-ranging changes to new practice guidelines are also being introduced this year that require all patients for cosmetic surgery and procedures to be psychologically screened by the medical professional performing the surgery to assess the reasons that they are getting the work done. This includes an assessment of whether the patient has an underlying psychological condition, like body dysmorphia.

When it comes to regulations around breast implants specifically, back in 2016 the Federal Department of Health and Aged Care, acting with the Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA) established the Breast Implant Expert Working Group, which provides the TGA with up-to-date research about breast implants in Australia, including on SSBI.

“It’s got risks around the time of the surgery and it’s got significant downsides for some people… So I think my main message would be that this is real surgery and you have to treat it like any other real surgery by weighing up the pros and cons, just the same as if you were having your gallbladder removed or a knee operation or anything else like that,” she said.

In 2019 the TGA completed a review of breast implants and their use in Australia that resulted in regulatory changes and led to a new classification that treats them as "high-risk devices" and ensures that they undergo strict assessment processes before they can be approved for use in Australia.

As for the SSBI research, the Department of Health and Aged Care said that the TGA monitors clinical research currently in process into SSBI and is focussed on any emerging complications associated with breast implants to ensure quick and appropriate responses.

In the meantime, both Charlotte and Bella said they are just keen to spread the message on the risk of SSBI and assure those that are living with these symptoms that they're not alone.

"I really just want to raise awareness and I think for me, if it wasn't for social media, I would have been able to determine what was going on with me and I wouldn't have been able to make the proactive decision to explant," Charlotte said.

"I think the biggest thing for me is, at the time, for my younger self, it didn't fix what I thought it would fix and it was some further learning I had to do deep down. I feel like the reason I've been so vocal is that I've had to make it a bit of an educational piece for a very tough lesson I had to learn."

Elfy Scott is an executive editor at Mamamia.

Mamamia’s core purpose is to make the world a better place for women and girls, by producing content that makes women feel seen, heard and understood. This article is one of thousands we’ve written over the past sixteen years shining a light on things other people don’t talk about.

Subscribers help fund our team of female creators and enable us to continue telling the stories that matter to Australian women. For just $5.75 a month, you can support independent women’s media.

Become a Mamamia subscriber to get unlimited access to the best podcasts, stories, videos and events for women.