Kaitlin Roig-Debellis is the first-grade teacher at Sandy Hook Elementary School. She saved her entire class of six- and seven-year-olds from the horrific shooting that took place there on December 14, 2012, by piling them into a tiny bathroom in her classroom, mere feet from the brutal massacre happening outside the door.

In this extract from her gripping and powerful new book Choosing Hope, Kaitlin recounts what it was like entering the classroom for the very first time after the tragic event took place.

I went back to school with a clash of emotions.

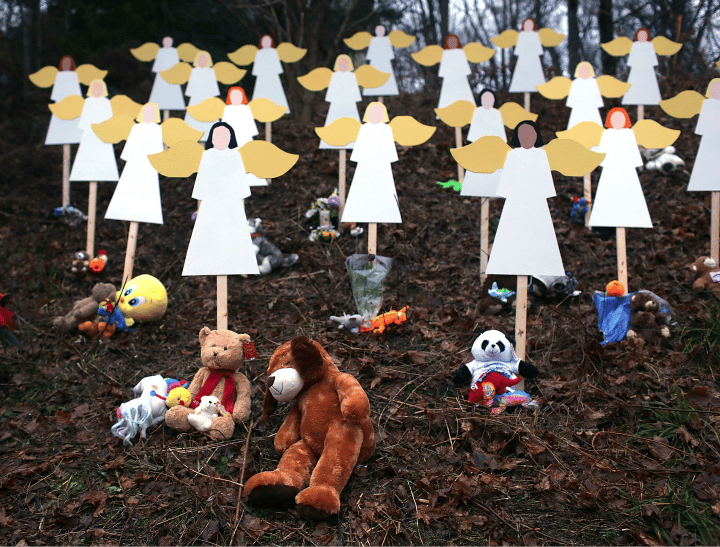

The thought of returning to class with my students felt absolutely right, but the crater of emptiness left by those who were missing was breathtaking. With the new school came poignant reminders of what once was. There was no happy banter with our beloved principal at the front door, only two uniformed police officers and reverential silence. No joyful sounds of children from the neighboring classroom, just an empty place where they should have been. It all felt surreal. Awful.

Terrible. Wrong. Sickening.

At the same time, the distance from what happened gave my students and me a sense of separation from the tragedy. In some way, it felt like a new chance. The district had done a nice job of replicating our classroom in the new school. Our desks and cubbies, books and toys from Sandy Hook had been moved to our new room before classes started up. Someone had even hung up the jackets the students had left in their haste to get out of our old school.

At 8:55am, like always, my students filed in, as excited to see me as I was to see them. I put on my best face, determined to make the day as comfortable as I could for my kids. I’m not sure what I was expecting, but within minutes I could feel an energy change from our old classroom, a change resulting from the hell my students had been through. Because their trust and sense of security had been shattered, it almost felt as if we were strangers at the beginning of the school year who were just getting to know one another. I knew I had my work cut out for me.

Top Comments

There were more than 50 other teachers and adults in that school that day who also hid and protected their students, including the 4 teachers who were killed. Kaitlin Roig is the only one who is having photo shoots, walking red carpets, going on tour, taking photos with "fans", signing books, getting awards, and behaving like a celebrity. She continues to hurt the families who lost children everytime she retells her story of how she's a hero and saved her kids. I cannot believe anyone who read that book cannot come away with seeing firsthand just how obsessed she is with herself and how she has made this tragedy all about her heroics. It is crazy to me that she sees nothing wrong with what she's doing ( the book and celebrity behavior, not her non-profit program ). No other teacher in that school that day has chosen to profit off of this tragedy, were given awards, or are behaving like a Hollywood star. Go to Newtown and ask around and you will see the mere mention of her name is met with many eyerolls. What upsets me most is how she accused other professionals in education of not caring about the kids like she does. She came across ( to me ) as a traumatized teacher who had no business going back to the classroom because she was instilling more fear and doubt into children who were already vulnerable. I can completely understand why they asked her to leave. For her to insinuate they didn't have the kids' best interests at heart ( but she did ) is proposterous. She can deny it all she wants, she's entitled to her opinion. But my opinion I'm entitled to is that she has grabbed this tragedy by the horns to use to propel herself to stardom....at the expense of the families who lost a loved one that horrible day. If you ask me, in no way did her book demonstrate she is choosing hope. Quite the opposite. She continues to appear to be a traumatized woman who needs to keep talking about what she and 500 others went through. You know who impresses me? The child who was in the smack middle of her classmates being murdered and played dead. She and the 11 other children who escaped the other class are the ones who deserve awards and book deals and celebrity treatment. Ms. Roig needs to come down off her high horse and stick to her non-profit. Stop rehashing this tragedy over and over and over to score an interview on tv, radio or magazines.

This was very well said, and fairly spoken. The real heroes are the teachers, staff, children and parents who were able to return to their daily activities, despite their pain and fear. Sadly, Ms. Roig was unable to and left the kids of her class without hope. Her complaints about the security of the Chalk Hill facility were facile. That building was a fortress with multiple layers of protection. If she were truly strong, she would have stayed, instead of running away and seeking publicity.

I cried all the way through reading this. I read another excerpt from her book in a newspaper last Sunday where she described the day that it all happened. Having read that article it is incredible that the adults around these children aren't doing absolutely WHATEVER these kids need to feel safe. If they say they need more, then give it to them, no questions. What they went through is unimaginable for an adult, let alone these beautiful innocent little souls...!

Yep, crying again here. I couldn't believe it at the time that it happened, that someone would specifically target a place where small children were. This was the point I lost hope for the Americans and their belief in their gun laws. If this was not enough to shock them into change, then there is nothing left that could do it.

I don't know any of Miss Roig's class but I totally understand her feeling of wanting to wrap each and every one in a big bear hug to try and convince them that there is good left in the world. It's so heartbreakingly sad. Miss Roig deserves a massive hug too for being such an amazing person and teacher!